Jerry Takigawa: Liminal Language: 1980-2020

Jerry Takigawa: Liminal Language, 1980-2020

A search for meaningful engagement from an authentic perspective drives Jerry Takigawa’s creative practice. A deeply reflective artist, his multi-layered photography mirrors the competing forces that shape him—the interior world of personal expression, the outer world of social and environmental engagement, his Japanese heritage versus his homegrown American experience. From an effort to harmonize these dichotomies comes Takigawa’s singular vision and his award-winning body of work.

As a painting major at San Francisco State University, Takigawa first took up the camera in support of his photorealist art. He studied photography with Don Worth, and began to photograph the political movements of the late 1960s Bay Area. Although he ultimately abandoned painting for photography, painting and design honed his eye to subtlety and nuance and helped shape the trajectory of his art.

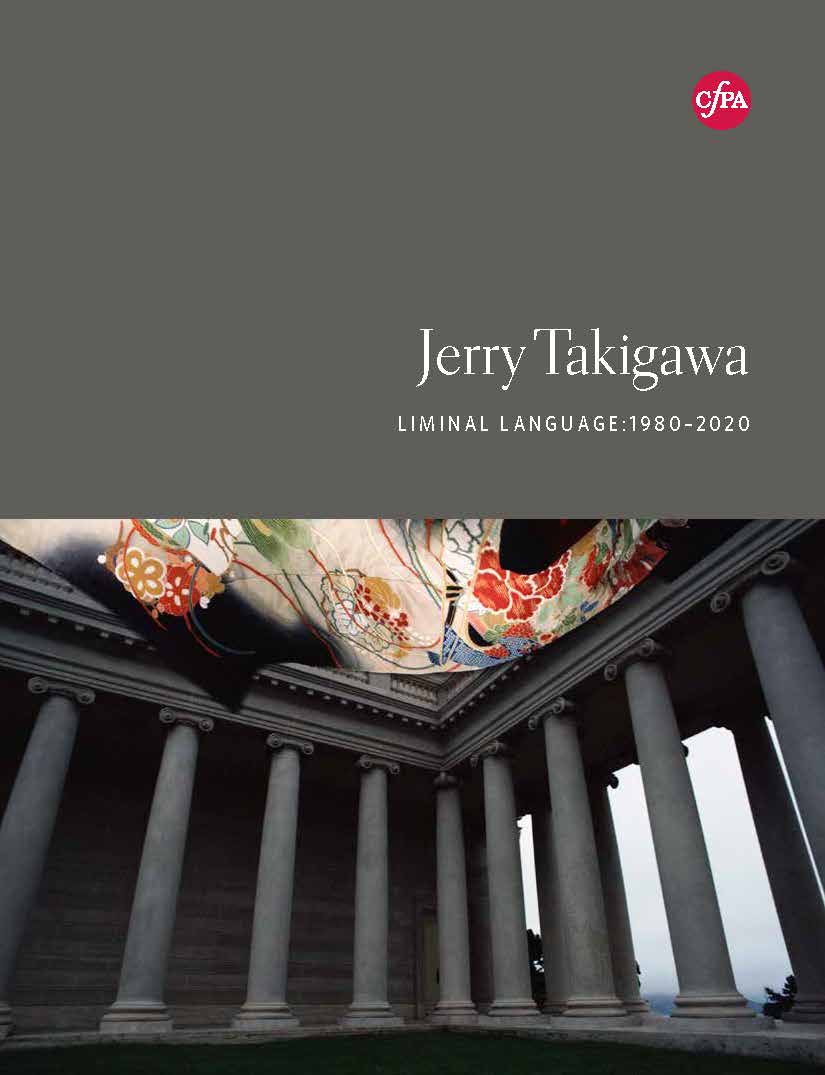

In his 1980s Kimono Series Takigawa switches to color, and sets up lengths of Japanese kimono fabric in the landscape. The use of this fabric was a first in a cultural sense; although unplanned it revealed a lovely affinity with the natural surroundings. He also photographed the fabric in urban environments, where it introduced color and elegance into the geometric regularity of the building’s façades. Both the urban and rural Kimono Series strive to unite intrinsic differences—handmade with nature, stability with flow, buoyancy with weight, Japanese with American. This work won Takigawa the Imogen Cunningham Award—the first presented for a color portfolio.

With Landscapes of Presence, the black and white still life series that followed, Takigawa continued to investigate themes of relationship and contradiction, and to engage with the Japanese aesthetic. He layers fabric, calligraphy, leaves, bark, and stones, and in a first, adds in background photographs of clouds or trees, to create personally significant sacred spaces. With the inclusion of preexisting photographs he also inserts the dimensions of time and space, and begins to invent a new language to represent them. Takigawa fully embraces the assemblage process in service of the environment in his next series, False Food. At the Monterey Bay Aquarium he saw pieces of plastic recovered from the stomachs of dead birds who had ingested it as food. Stunned, he asked for some and used it to create layered photographs that pair the plastic bits with antique Japanese art reproductions, calligraphy, preexisting photographs, and more. False Food underscores a plastic epidemic that is universally destructive and tragically, human-generated. In a sense, his images are his offerings—to sorrow and maybe to hope. They convey the extent of the crisis without generating a reaction of horror.

His current project, Balancing Cultures, lies at the junction of personal and universal, past and present, Japanese and American. On the death of his mother Takigawa was deeply shocked to discover snapshots of family members in America’s World War II concentration camps. With trepidation, because to reveal these images felt like betraying a family secret, he made them subjects of his work. Juxtaposing calligraphy, personal mementos, and Go tiles with racist tracts, prisoner identity cards, and government edicts, he unites his family with documentary evidence of the racist rhetoric and treatment they experienced, Balancing Cultures brings Takigawa to the heart of his exploration into his dual Japanese-American cultural experience. In truth, he has spent forty years on this artistic path, as this retrospective collection clearly shows. He has created a personal language of transformation, and through his photographs we discover that his story is universal.

A search for meaningful engagement from an authentic perspective drives Jerry Takigawa’s creative practice. A deeply reflective artist, his multi-layered photography mirrors the competing forces that shape him—the interior world of personal expression, the outer world of social and environmental engagement, his Japanese heritage versus his homegrown American experience. From an effort to harmonize these dichotomies comes Takigawa’s singular vision and his award-winning body of work.

As a painting major at San Francisco State University, Takigawa first took up the camera in support of his photorealist art. He studied photography with Don Worth, and began to photograph the political movements of the late 1960s Bay Area. Although he ultimately abandoned painting for photography, painting and design honed his eye to subtlety and nuance and helped shape the trajectory of his art.

In his 1980s Kimono Series Takigawa switches to color, and sets up lengths of Japanese kimono fabric in the landscape. The use of this fabric was a first in a cultural sense; although unplanned it revealed a lovely affinity with the natural surroundings. He also photographed the fabric in urban environments, where it introduced color and elegance into the geometric regularity of the building’s façades. Both the urban and rural Kimono Series strive to unite intrinsic differences—handmade with nature, stability with flow, buoyancy with weight, Japanese with American. This work won Takigawa the Imogen Cunningham Award—the first presented for a color portfolio.

With Landscapes of Presence, the black and white still life series that followed, Takigawa continued to investigate themes of relationship and contradiction, and to engage with the Japanese aesthetic. He layers fabric, calligraphy, leaves, bark, and stones, and in a first, adds in background photographs of clouds or trees, to create personally significant sacred spaces. With the inclusion of preexisting photographs he also inserts the dimensions of time and space, and begins to invent a new language to represent them. Takigawa fully embraces the assemblage process in service of the environment in his next series, False Food. At the Monterey Bay Aquarium he saw pieces of plastic recovered from the stomachs of dead birds who had ingested it as food. Stunned, he asked for some and used it to create layered photographs that pair the plastic bits with antique Japanese art reproductions, calligraphy, preexisting photographs, and more. False Food underscores a plastic epidemic that is universally destructive and tragically, human-generated. In a sense, his images are his offerings—to sorrow and maybe to hope. They convey the extent of the crisis without generating a reaction of horror.

His current project, Balancing Cultures, lies at the junction of personal and universal, past and present, Japanese and American. On the death of his mother Takigawa was deeply shocked to discover snapshots of family members in America’s World War II concentration camps. With trepidation, because to reveal these images felt like betraying a family secret, he made them subjects of his work. Juxtaposing calligraphy, personal mementos, and Go tiles with racist tracts, prisoner identity cards, and government edicts, he unites his family with documentary evidence of the racist rhetoric and treatment they experienced, Balancing Cultures brings Takigawa to the heart of his exploration into his dual Japanese-American cultural experience. In truth, he has spent forty years on this artistic path, as this retrospective collection clearly shows. He has created a personal language of transformation, and through his photographs we discover that his story is universal.

Publisher: Center for Photographic Art

Visit website