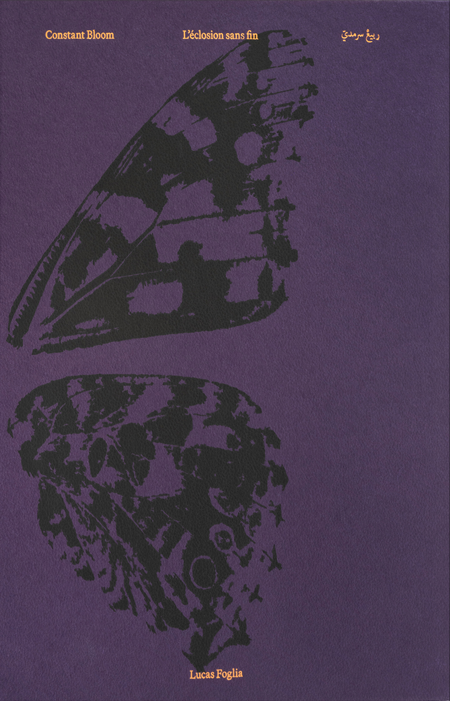

Each year, the fragile-winged creatures that are scattered through Lucas Foglia’s latest book Constant Bloom embark on a monumental journey. In search of wildflowers, Painted Lady butterflies follow the same route they have followed for millions of years between Africa, the Middle East and Europe—a migratory cycle of 15,000km that has only recently been mapped out thanks to the Worldwide Painted Lady Migration Project.

Over the course of three years, Foglia traced the path of the longest butterfly migration. Across vastly different landscapes he photographed both the butterflies and the people they encountered along the way. Some were refugees following a similar route to Europe. More resilient than its delicate appearance might suggest, the Painted Lady is—like us—having to adapt to our changing world. In Foglia’s photographic study of the longest butterfly migration, human and non-humans share a landscape, connected across borders.

In this interview for LensCulture, Foglia talks to Sophie Wright about learning to spot Painted Ladies, the people that make up Constant Bloom and the hope that sprung from observing this extraordinary natural phenomenon.

Sophie Wright: Can you tell me about the beginnings of your relationship to nature which seems to have been a constant presence in your life and practice?

Lucas Foglia: I grew up on a small family farm in New York. The forest behind our house felt wild, even as our neighbors’ properties were developed into suburban houses for people who commuted into New York City.

SW: How did these interests first rub up against photography? And why is it your chosen medium to speak about the things you care about—what can it do?

LF: My mother, Heather Forest, is a storyteller and children’s book author. My father, Larry Foglia, is an environmental educator and activist. They still grow vegetables together, and now donate most of their produce to the local food bank.

What I do now is rooted in the way I grew up. I discovered photography when I was a teenager. The medium intrigued me as a way to share stories about our relationship with the world, and how we live in it.

SW: Can you tell me about the origins of Constant Bloom? Did it grow out of any other projects or does it mark a departure in your work?

LF: I’m 42. For the past decades, I have made books and exhibitions about nature from the perspective of people. For Constant Bloom, I wanted to flip that around. I spent four years following Painted Lady butterflies—I was curious what the longest butterfly migration could teach us about connection across borders.

SW: From what I can tell, for you this is the first time a non-human entity has been the guiding force of a project. Can you tell me something about your subject and their odyssey that you have traced with your camera?

LF: Painted Lady butterflies are found on every continent except Antarctica, but their full migration between Central Africa and the Arctic Circle was only recently proven by a team of scientists collaborating across borders. That discovery struck me as both poetic and urgent: a small, fragile insect crossing regions often defined by human conflict and crisis.

I photographed both the butterflies and the people they encounter. I was drawn to the Painted Lady not only because of its resilience, but because it became a way to visualize our interconnectedness: a creature that knows no borders, and whose survival depends more and more on the flowers we grow in our parks, farms, and gardens.

SW: The butterfly traverses a huge distance across Africa, the Middle East and Europe in search of flowers. How did you map out your movement over the three years of working on the project? Did the idea you started with change over time?

LF: Each year, they journey from the African savanna, over the Sahara and Arabian deserts, across the Mediterranean Sea, through Europe, and all the way to Scandinavia—and then they come back. It’s a migration of more than 9,000 miles, traveled by a creature that weighs less than a rose petal.

At first, I thought of the project as primarily a nature story. But over time, I realized it was also a story about people—those displaced by weather or war, those working to restore ecosystems, those simply planting flowers in their backyards. The butterflies became a metaphor.

SW: People are as much part of Constant Bloom as butterflies. Some are seen with nets, implying a closer relationship to your winged subjects. Others are migrants themselves. Can you tell me about your human subjects and how you met them?

LF: This discovery happened because scientists collaborated across borders—Kenya, Jordan, Spain, Switzerland, and many other countries—tracking the butterflies. I collaborated with those scientists, from the Worldwide Painted Lady Migration Project. They showed me how to look for the Painted Ladies, mostly by looking for the plants and flowers that the butterflies look for.

As sunset approaches, Painted Lady butterflies often gather at the highest rocky points of the landscape, where they are likely to mate. So when I asked people where they go on dates to watch the sunset, I often found butterflies there too. Once I found the butterflies, I photographed the people around them. Sometimes scientists or friends. Other times I met people while traveling.

For instance, I stood on a cliff in northern Tunisia, overlooking the Mediterranean. A wildfire had blackened the forest. Purple flowers bloomed between charred trunks. I photographed Painted Lady butterflies there, drinking nectar before migrating north. Three teenagers asked for a portrait with the sea behind them. Months later, one called to say his boat landed near my family’s village in Italy. He asked if the butterflies arrived safely.

So in the end Constant Bloom is a book and exhibition about Painted Lady butterflies. It’s also about how nature and people are connected across borders. The butterflies have been migrating for millions of years before any border existed—before the rise or fall of any human empire.

SW: Finally, could you tell me something about the title Constant Bloom?

LF: When Painted Lady butterflies arrive in a place, they need it to be blooming. Each year, they cross the Sahara and Arabian deserts, timing their migration to the brief bloom of wildflowers that follows seasonal rains.

From the perspective of their species, the world is always blooming. That’s why I titled the book and exhibition Constant Bloom. It also speaks to the core message of the project: continuation. Even when our wings are torn, it’s not too late to keep going. It’s not too late to act together on what matters most. As long as the world keeps blooming, there’s still hope.

Editor’s note: Constant Bloom is currently on view at Galerie Caroline O’Breen in Amsterdam until 21 June, Fotomuseum Den Haag in The Hague until 28 September and Galerie Peter Sillem in Frankfurt until 16 August.