What happens when speaking in your mother tongue feels like an act of betrayal? Stolen Language touches on an internal conflict inextricably tied up in an external one. Born from Julia Wimmerlin’s experience as a Russian-speaking Ukrainian, the project explores a struggle faced by many Ukrainians since the full-scale invasion in 2022. Watching the war unfold, the photographer faced a crisis of identity little understood by her neighbors in her adopted-home of Switzerland.

In parallel to re-learning Ukrainian, Wimmerlin uncovered the oppressive Soviet measures that had—previously unbeknownst to her—shaped her childhood; a series of policies known as ‘Russification’ put in place to erase Ukrainian language through the adoption of Russian. Translating her findings into imaginative and symbolic images, Stolen Language helped her through her personal process. With a 577% increase in Ukrainian learners on the app Duolingo in 2022, hers is not an isolated experience.

In this interview for LensCulture, Wimmerlin speaks to Sophie Wright about her multiple past career paths, using photography as therapy and finding a creative way to speak about her shifting relationship to language.

Sophie Wright: Can you tell me about your beginnings in photography? Do you remember the feeling that first led you to pursue it?

Julia Wimmerlin: I’m an economist by education and marketing specialist by profession. If you’d told me 15 years ago that I would become a photographer, I would’ve laughed in your face. I always thought photography was very male, very technical—and therefore boring. That changed when my family moved to Japan. Its beauty made me obsessed with the idea of capturing it. I tried taking photos with the point-and-shoot camera I had at the time, but they looked nothing like what I felt. I found a professional English-speaking photographer who explained the basics to me. I borrowed my husband’s DSLR—and I never did marketing again.

SW: How would you describe the things you want to explore as a photographer and how did these interests come your way? Why is photography the way you’ve chosen to speak about them?

JW: For the first 10 years after my first photography lesson, I was just happy to photograph whatever I saw around me, usually in a poetic, beautifying way. I became a travel photographer, working with various travel media. I simply enjoyed the process of sharing the beauty I witnessed. By that point, I was hooked on the magic of light, and photography was the only way I knew how to capture it. Light and color became the signature of my travel photos.

SW: In more recent years, your work seems to have turned in a therapeutic direction as you seek a way to deal with the tragic events unfolding in your homeland of Ukraine. Can you talk a little about this shift in your work?

JW: With the pandemic-related travel ban, I had to find non-travel subjects for the first time in my photographic career. That’s how I started getting interested in contemporary art photography. When the full-scale invasion began, after the initial shock, I realized that photography could be my greatest weapon in this war. There are many incredible photographers in Ukraine documenting and reflecting on how people are surviving these terrible times. I felt a strong need to tell the stories about Ukraine that would resonate outside its borders. I wanted to put human faces on the war casualties people had grown used to reading about. I wanted to make this war relatable to those who think something like this could never happen to them.

SW: One of these projects (UN)CORNERED deals with other Ukrainian women that have also moved to Switzerland where you live, while Art Therapy is made-up of self-portraits and LOVE. MY FAMILY reflects on your new reality living with your mother who moved after the full-scale invasion began in 2022. In what different ways did these projects help you tend to and engage with the topics affecting you?

JW: The project (UN)CORNERED helped me survive 2022. It was the only thing that finally kicked me out of the limbo I had been in since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. Over the course of a year, I photographed 40 women who had escaped from different parts of Ukraine, capturing them in the corners of their temporary homes across Switzerland. I wasn’t looking for heroic or dramatic stories—I wanted to show a slice of life as it could be in any European country. I cried from happiness when, after the exhibition in Nidau, Switzerland, a Swiss woman told me: “Getting to know these women’s stories, I kept thinking—it could have been me.”

LOVE.MY FAMILY was an emotional response to the months I spent on the road working on (UN)CORNERED, listening to stories of courage, humanity, humility, sacrifice, and love for life. If that year taught me anything, it’s the importance of love: love for your family, your friends, people in need. Love always seemed like such a banal subject to me—over-talked, over-photographed. That’s why I wanted to pay tribute to my family, to the new connection I had with my mother, to the unconditional support of my husband, and to the quiet but always healing presence of my four pets.

Over the past four years, photography has become a means of creative self-expression, a way of making sense of reality, and, as a result, a form of therapy to come to terms with what that reality reveals. Art Therapy was an homage to some of the most inspiring modernist artists, helping me align with Ukraine’s new reality, and the state of the world in general.

SW: Stolen Language began with your own complex relationship to language and the process of taking Ukrainian language courses. Can you elaborate on this relationship and the internal conflict it ignites?

JW: I’m a Russian-speaking Ukrainian who, until 2022, had never spoken Ukrainian outside of school. I once believed that the language I spoke in Ukraine didn’t really matter, as long as I was understood. It was common to hear one person speak Russian and another reply in Ukrainian. But the war brought me to the painful realization that if I continued to speak Russian, I couldn’t be distinguished from Russians. I became aware that my national identity had been heavily deformed—and I hadn’t even noticed it.

Many people struggle to understand why so many Ukrainians speak Russian, even three years after the full-scale invasion. I remember trying to explain this conflict to my Swiss friends. I live in the French-speaking part of Switzerland, with France as a neighboring country. I asked them to imagine living their whole lives speaking French—one of their own country’s national languages—enjoying French culture, until one day France attacked their home. Suddenly, by default, you become indistinguishable from your enemy. You might even start to feel like a traitor. You can switch to another language, but it will never be your mother tongue.

SW: What led you to explore this experience through photography and how did you go about deciding the way you were going to do it?

JW: Photography is a universal language—visuals bypass the linguistic barrier and go straight to the heart and mind. Some of the images in my series need no explanation, no cultural context, and that’s only possible through photography.

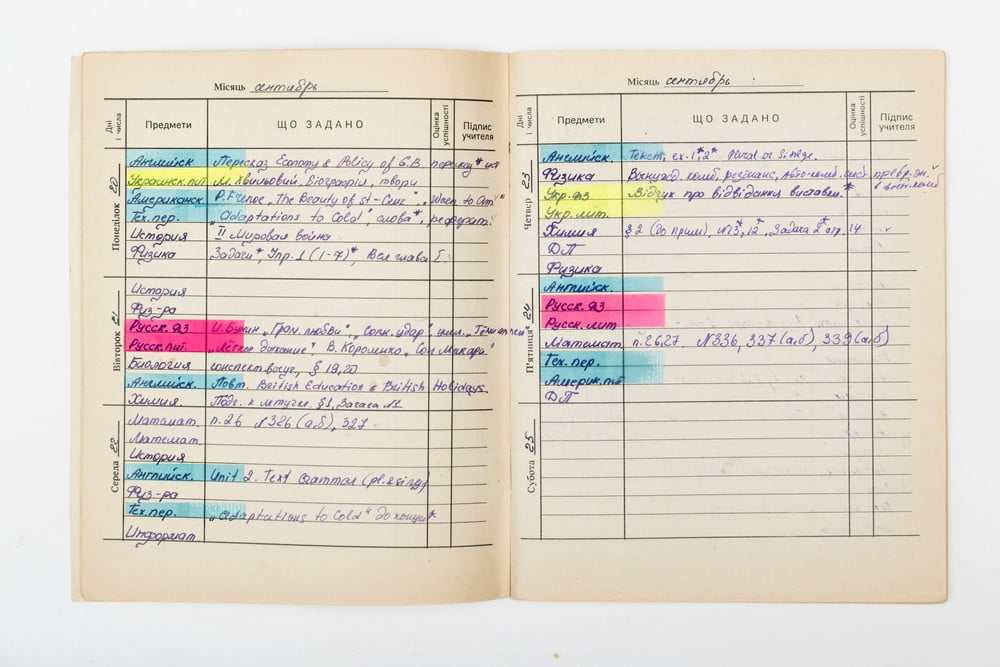

Since speaking is one of the first things you learn as a child, I decided to reexamine my past—my education, my beliefs, and the stereotypes I had about myself—in order to gain a more conscious understanding of reality. By combining family archive photos, my own photography archive, and a mixed-media approach, I tried to show how someone can not only steal your native language, but your entire national identity.

SW: As you began the process of working on your Ukrainian language skills, a world of research unfolded that introduced even you to the full extent of Russification. What kind of historical information did you unearth during your journey with the project? Did it make you reflect on your experience of education?

JW: Learning, or in my case, re-learning, a language goes hand in hand with learning about the country’s culture and history. I studied in a Soviet school, where the only language of instruction was Russian. Ukrainian language, literature, and history were reduced to censored Soviet folklore. As I progressed in learning Ukrainian, I began researching its history.

Having grown up in the Soviet Union, I had felt its impact—but it wasn’t until I dug deeper that I truly understood the extent of the historical manipulation. The covert Soviet strategy of Russification involved a systematic erasure of Ukrainian national identity. It extended to public perception as Ukrainians were portrayed as intellectually inferior, and even to the forced alteration of Ukrainian surnames into Russian ones. A language-reform program was launched to make Ukrainian resemble Russian as much as possible, gradually erasing its uniqueness. Letters were removed from the alphabet, and words were replaced, giving rise to ‘surzhyk’—a linguistic amalgamation of Russian and Ukrainian languages supposedly spoken by uneducated common Ukrainian people. Speaking Ukrainian became shameful, a symbol of backwardness and lack of culture.

SW: Your approach to image-making is imaginative, full of details and different approaches to creating meaning. Can you describe your work process and how you translated your discoveries, feelings and ideas into an aesthetic approach?

JW: I start with a visual board where I pin down key concepts and my initial visual ideas. Sometimes the translations are literal, sometimes metaphorical, but always aesthetic—probably a leftover from my marketing background. Some images end up as I planned them, others are the result of happy accidents.

One of the key images in Stolen Language is a stereotypical Ukrainian female silhouette with a large chemical stain on her throat. I originally planned to burn a hole in the photo paper using bleach, but the chemical reaction with the glossy surface turned the stain blue and yellow—just like the Ukrainian flag. I could’ve never predicted that. It felt like a sign.

SW: A few of the images reference the poet Lina Kostenko. What inspired you about her writing and how did it shape your own images?

JW: In a certain way, reading Lina Kostenko’s article The Humanitarian Aura of the Nation or the Deformation of the Nation’s Main Mirror, delivered as a speech to the students of Kyiv Mohyla Academy in 1999, was the inspiration behind my series. I stumbled upon this article while researching the history of the Ukrainian language. Kostenko, a former Soviet dissident and one of Ukraine’s most important contemporary poets, used a metaphor in her speech that struck me deeply.

She told a story about a time when the Americans were launching a research station from Cape Canaveral, equipped with a particularly powerful telescope and a precisely accurate system of mirrors. At the last moment, they discovered a defect in the main mirror and suspended the launch. Only once the mirror was corrected did they send the telescope into orbit.

She draws a parallel with society, saying that each one looks into a complex spectrum of such mirrors to form an objective picture of itself. The main mirror of Ukrainian society, she argues, was severely deformed by the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, leading to a deep-rooted inferiority complex and a sense of shame around speaking the Ukrainian language.

SW: How has working on this project affected your relationship to language? What do you hope viewers take away from these images?

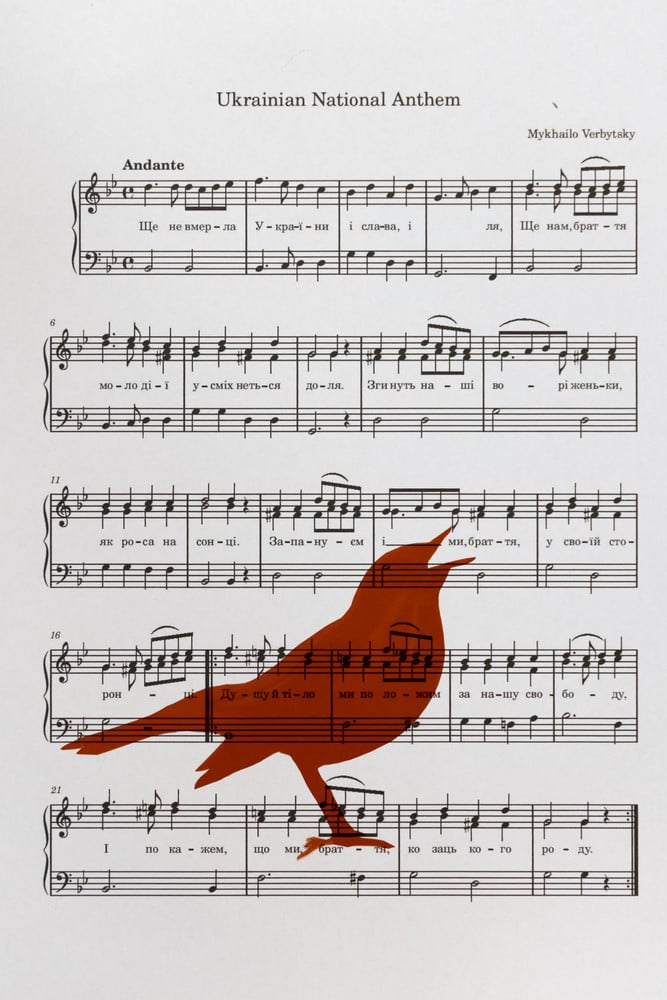

JW: I’ve always identified as Ukrainian but only now do I truly understand the depth of that identity. Working on this project allowed me to fall in love with the Ukrainian language as I discovered its true sound, beyond the castrated, dumbed-down Soviet version. Reclaiming and relearning my own language felt like an act of resilience and self-discovery.

Besides offering a bit of cultural and historical context to help people better understand the millions of displaced Ukrainians now spread across the world, I also wanted to show how the manipulation of public consciousness can make you lose your language, and so much more.

Through Stolen Language, I didn’t aim to offer an objective or undistorted reflection. Instead, I used constructed photography to consciously engage with distortion itself. By layering images, mixing media, and building symbolic compositions, I tried to recreate the emotional and psychological experience of having your cultural identity manipulated and fragmented over generations. These images are not meant to document—they’re meant to question, to provoke, and to hold space for personal and collective reflection.