When Igor Malijevský first visited Ukraine in 1997, it was like “stepping into a magical story.” The Czech photographer was visiting Transcarpathia, a region along the southwest border of Ukraine. Malijevský had a personal connection to the area. For a few decades after World War I, the region belonged to Czechoslovakia. His grandfather worked there as surveyor, photographing the landscape and its communities. Under Soviet rule, Transcarpathia became almost completely inaccessible. It wasn’t until Ukraine became independent in 1991 that the region opened to travellers again. Over half a century had passed, and Malijevský was intrigued to see how life had changed.

What the photographer experienced was an atmosphere of timelessness, and endless encounters with unusual characters. A man who offered him a ride in a military tank; a park ranger who arrested him, just so he could have a drink and chat; a teacher who hadn’t been paid for half a year, but insisted on putting him up.

“I still remember every person I met,” says Malijevský, who was 27 at the time. “The strongest feeling was an existential sense of returning home, to a place where time stands still, surrounded by neverending stories.” This feeling stuck with the photographer until his second visit to Ukraine in 2014, when he travelled to Lviv. What unravelled then was not only the beginning of an extensive documentary project, Signs of Lviv, but a relationship with his wife Olga, and a lifelong connection to a country now in the midst of war.

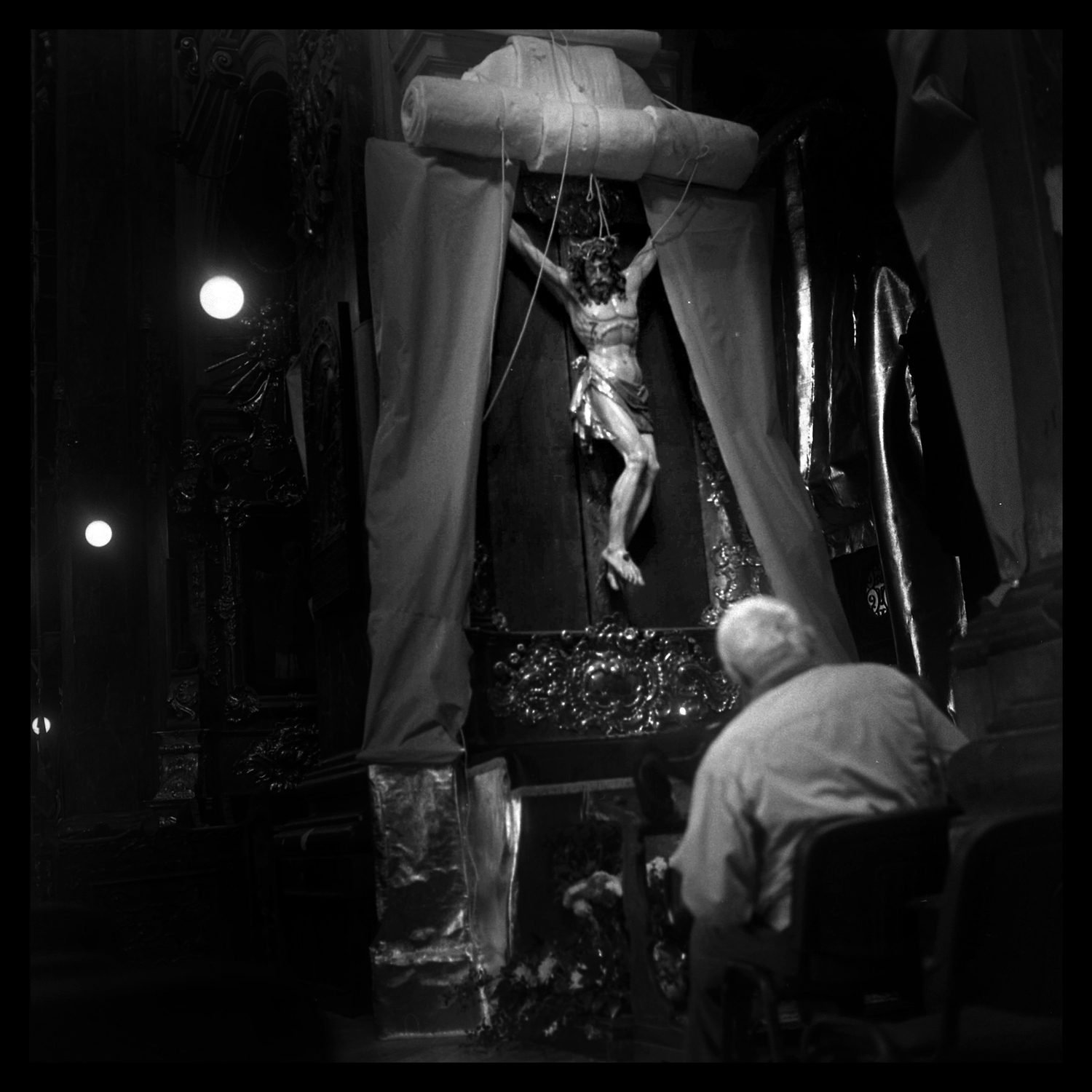

Malijevský’s latest return to Ukraine sees him deal with this current historical moment. Black and White War is an ongoing collection of photographs from Ukraine since Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. The photographer describes himself as a visual poet, and his wartime images pay testimony to his quiet observations of daily life. They do not depict crumbling homes, injured civilians, or soldiers marching to war. Instead, they are evocative of an emotional experience, inviting viewers to connect with the everyday experiences of war that can be overlooked by headlines in the mainstream press.

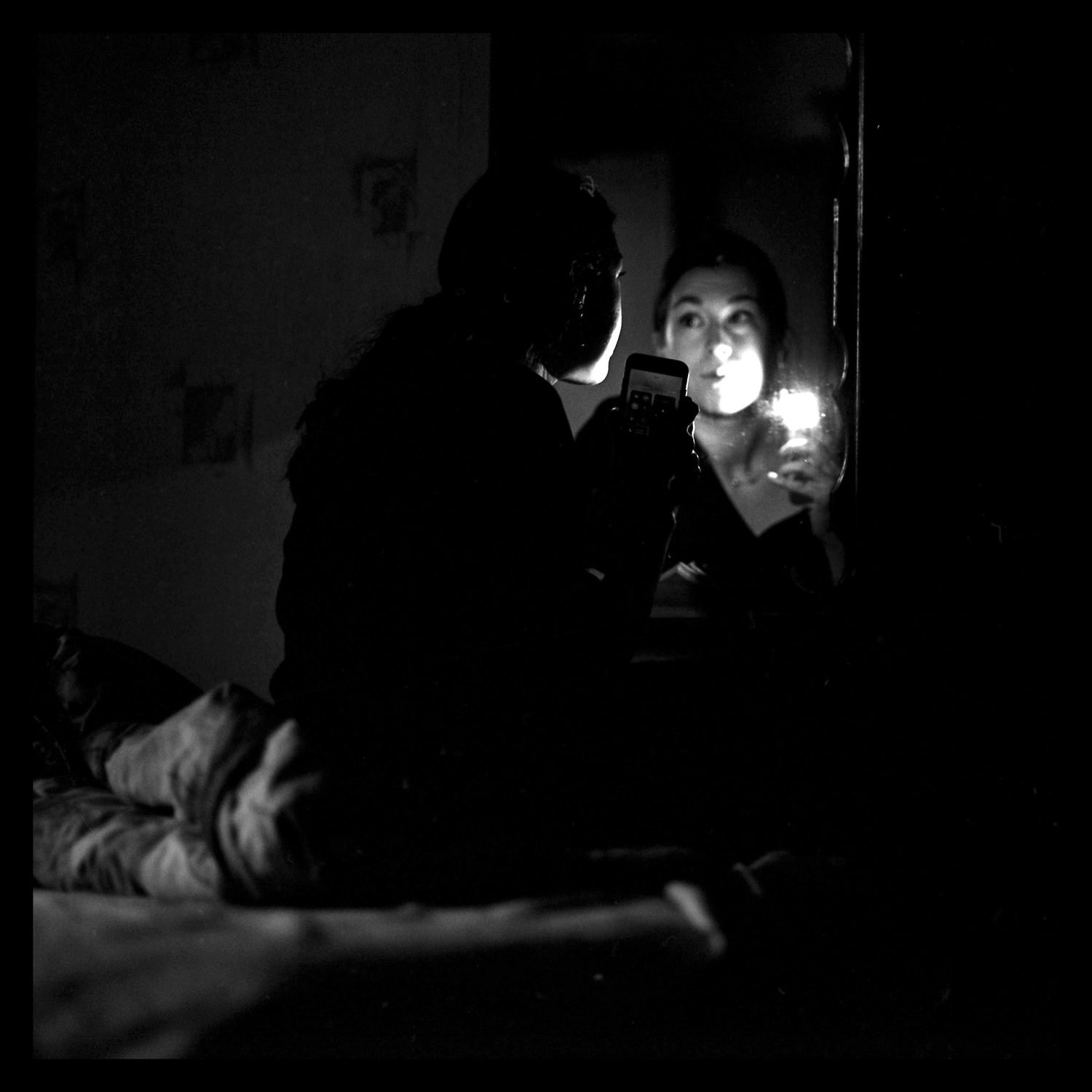

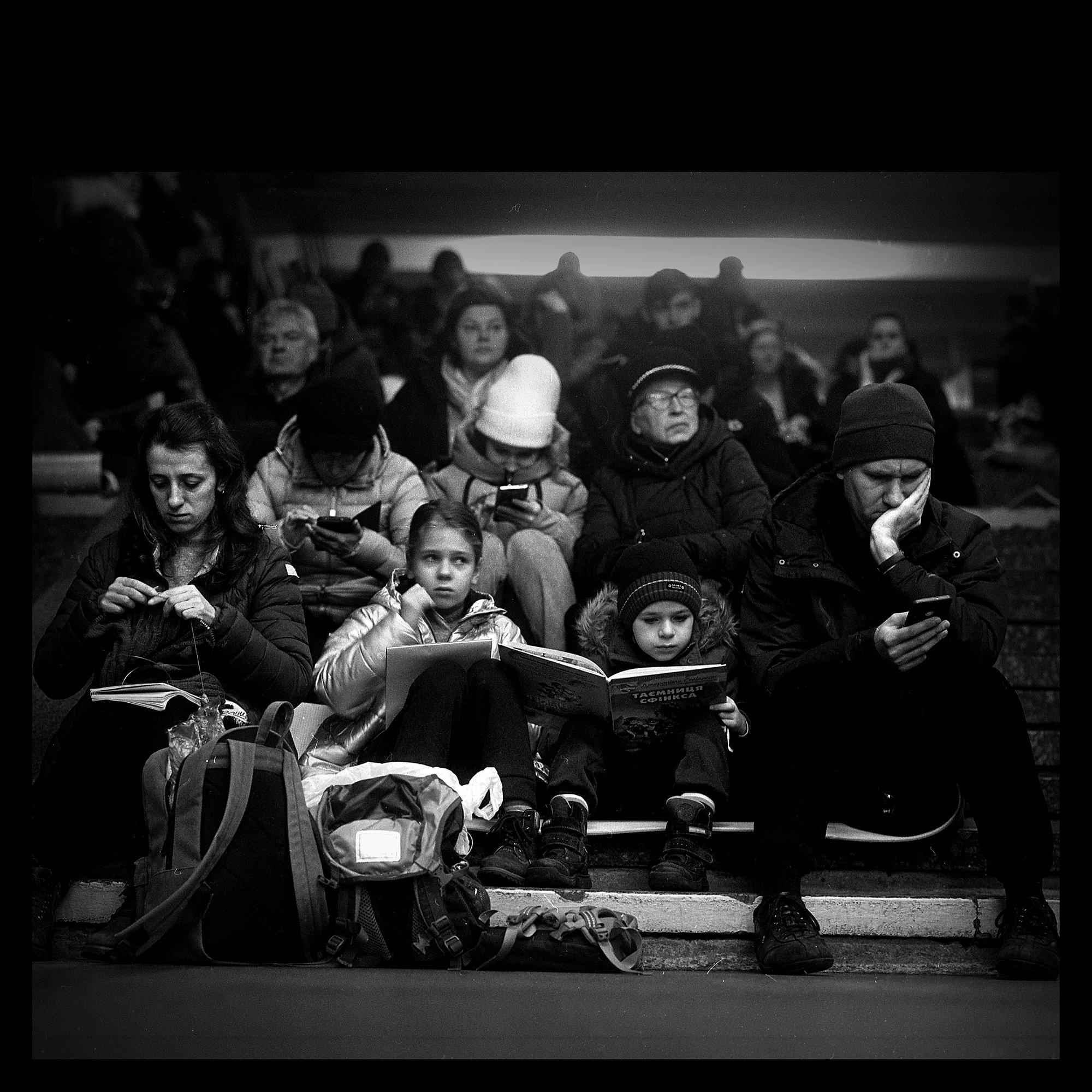

We meet Zoza, an artist who pensively drags on a cigarette in her beloved studio, the day before she plans to join the army. Then there’s Olha, an interpreter who uses a phone torch to apply makeup during a blackout. One particularly poignant image depicts a young couple kissing in an air-raid shelter. The photograph was made in the summer of 2022.

Despite the war, Ukrainian theatres remained open, often hosting concerts to fundraise for the army. Malijevský and his wife Olga had gone out to see their favourite Ukrainian band, Latex Fauna. The concert was abruptly interrupted by sirens after the third song. “People act strangely in air-raid shelters, often shutting themselves off into their own worlds,” he says. The image captures a moment of tenderness but also revolt. It shows how simple acts of love can offer hope amid the tumult of war.

Malijevský believes in the importance of war reportage, but sees himself as an artist rather than a reporter. “All that is left for me to do is to make poems about what it’s like when war comes to a country that is close to your heart,” he says. “I know it isn’t much, but it’s all I can do.”