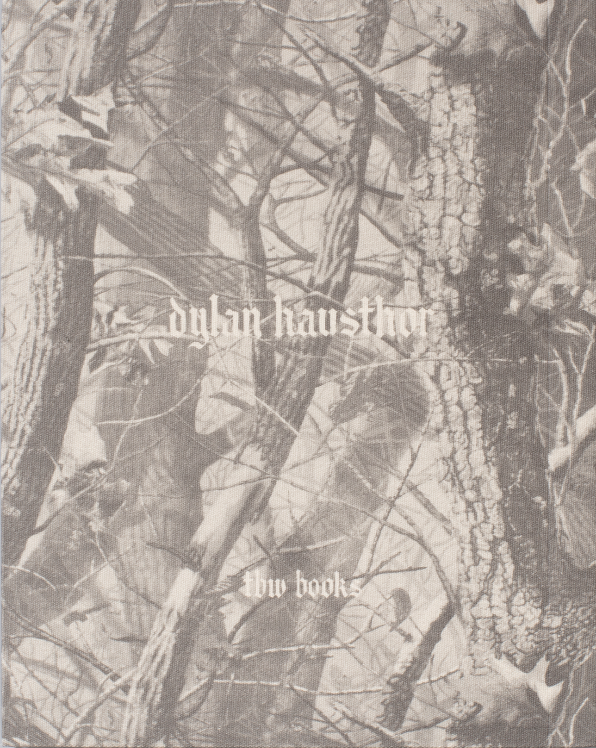

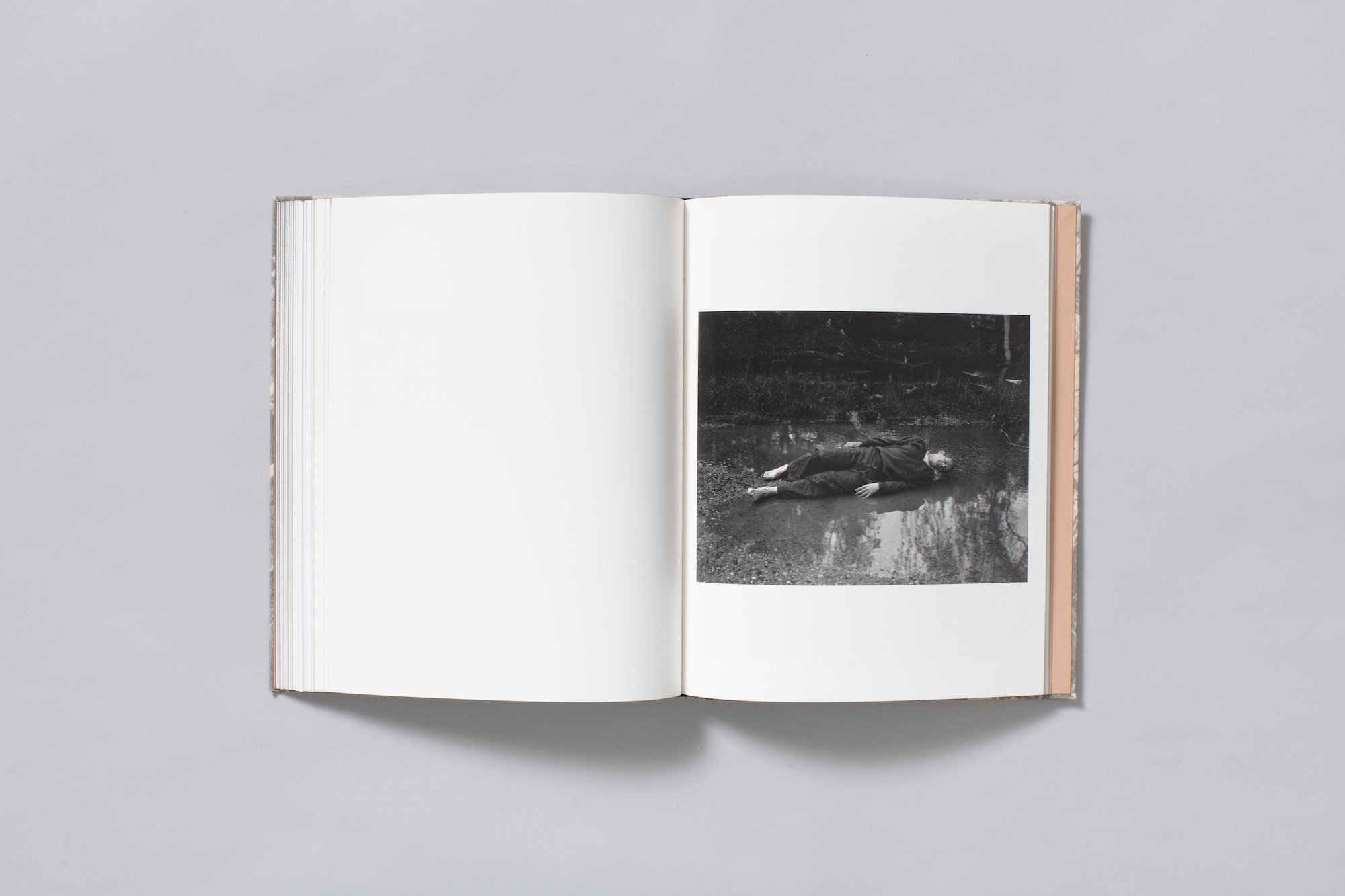

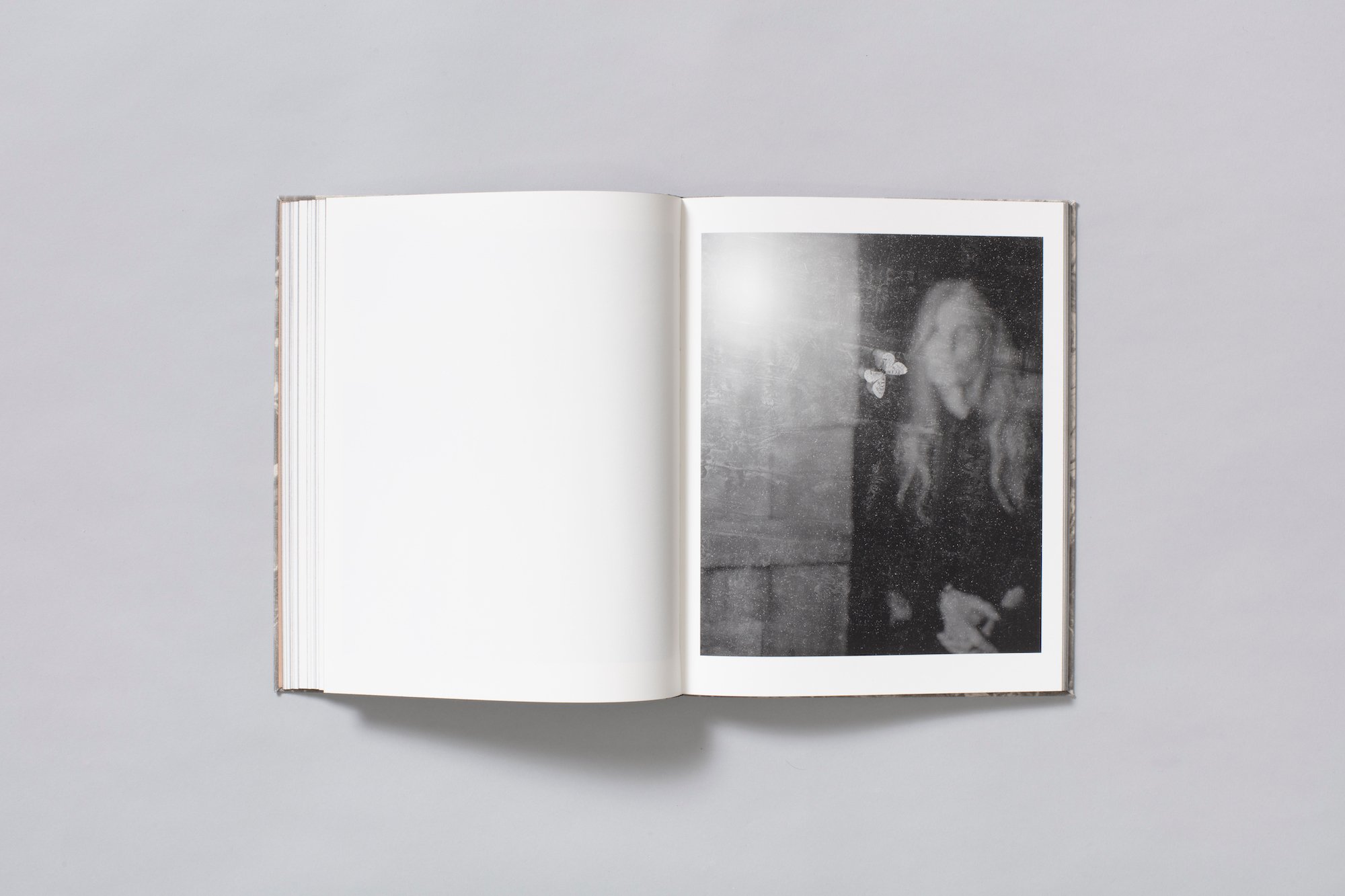

The world laid forth in What the Rain Might Bring is a wet and spirited one. Full of mysterious creatures—both human and beyond, both engaged in all sorts of rituals and rites as night cycles into day—it is created by Dylan Hausthor’s camera rather than captured. There is no way of knowing this place fully exists. Informed by myth and investigative journalism in equal measure, the precise black and white images gesture towards a story that continually slips just out of our reach, dissolving time and space with its own peculiar logic.

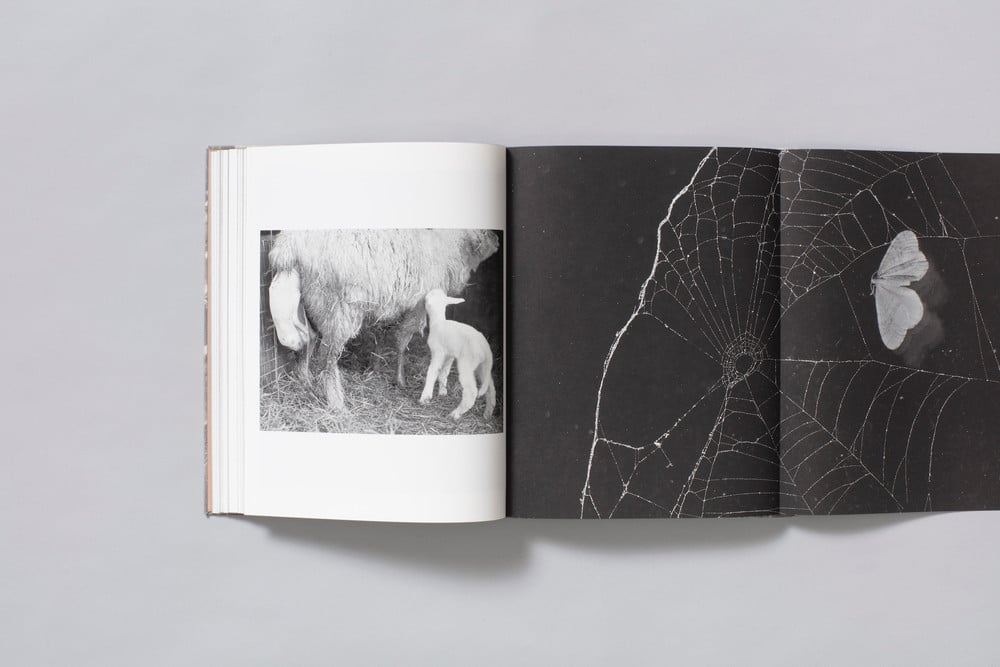

Here, place is a web of many different things all mixed up with each other. Fish fall through the sky, frogs populate cars. A woman disappears into a field of wispy flowers, a man’s head is caked in sloppy mud. A spider sitting in the center of its delicate construction steals the show from a written-off car, violently overturned in the background. Hausthor’s interest in our ‘post-fact’ world lurks under the surface of these beautiful, uncanny pictures, the book’s ambiguity an accurate reflection of the ungraspable moment we are living through.

In this interview for LensCulture, Hausthor speaks to Sophie Wright about nature photography, finding inspiration in Medieval manuscripts and the fragile balance between hiding and revealing.

Sophie Wright: What the Rain Might Bring takes its name from an old field guide to identifying mushrooms, while you have also mentioned an anecdote of an acquaintance telling you that mushrooms have no gender. Can you tell me a bit about these two pieces and their role in the genesis of and shape of the book?

Dylan Hausthor: In 2020 I was pumping gas in my hometown and saw my old ballet teacher sitting on a curb. I was only in ballet classes for a year, but remembered her fondly—I would see her somewhat often around town whenever I came to visit family. She is a bit of a local celebrity, who every autumn would wear a beautiful costume of a giant maple leaf when walking around our little town. That day at the gas station she had a small collection of mushrooms with her; we talked about how beautiful they were, the miraculous mycological network under our feet, and the astoundingly complicated way that mushrooms reproduce.

We talked about how queer they are, a topic I was particularly excited to explore as I was in the midst of my own process of understanding my gender. This conversation provided me with a lot of links between the ideas I was having in my studio about histories of queer-ing landscape, storytelling, and miracles. This led me back to an early mushroom identification guide by David Aurora titled All That The Rain Promises and More, who in the introduction to the book, writes: “…secret passions and dormant dreams, awaiting inspiration, instigation, and conditions that instigate growth. Rain has become my catalyst, drawing me up, bringing me out.” I hope that the images in the book do just that—both hide and reveal.

SW: Did the book grow out of any previous work or would you say it marks a new path in your practice? (and if so, how?)

DH: Yes indeed, the egg that ended up hatching into What The Rain Might Bring was laid toward the end of my time in grad school—a time during which I was making wildly different work and had a sort of mini-project based way of making. I felt that I left school with a feeling of having planted seeds for many different plants… Some of those seeds I’ve let die, some (like this book) I’ve spent a lot of time tending to, and some are just now beginning to sprout. I’m now looking forward to a few totally novel projects, including a book about angels, but am still interested in looking back at ideas that feel barely dusted-off—I’m thinking specifically about a book and video project I’m making now that is illegally broadcasted through a public access station that I’ve set up in my studio.

SW: There is a weird sense of place that unfolds across the pages, one full of rituals and community that seem to exist somewhere but also nowhere—a liminal spot between reality and imagination. Can you talk a bit about place, and your relationship to it, in this book?

DH: Place is key to everything, I think. I think about it ecologically—place determines the nutrition of soil, which determines the type of plants that grow, which determines the way they communicate, which determines community. I think of it the same way in regard to the spaces, people, and things that I image—it all starts with place. After it gets filtered through me, my experiences, my pain and joy… that’s when things really start to lose certainty and stability.

SW: Who are the people in your photographs and can you describe a bit about your work process in these collaborations?

DH: Love. The amount of love I have for those willing and interested in working with me is one that is unlike any other. This is true, not just in regard to the people that make their way to the pages of the book, but also to the process of making anything, I rely hard on my friends and family in nearly all aspects of art making. I photographed a friend’s birth the other day—an experience soaked in the classic photographic hybrid of participant, spectator, partner, and actor. I can’t be grateful enough for these types of relationships.

SW: Almost every frame is a collision between different animals, plants and—often the most awkward/eerie presence—people. What is your relationship to nature photography?

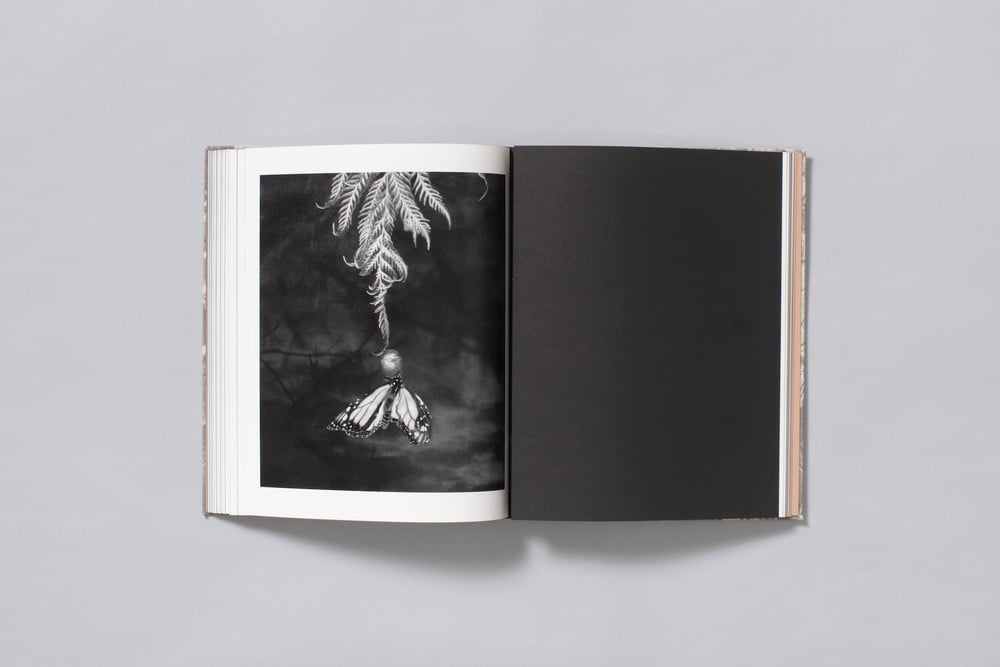

DH: Obsessive, I’d say! So many of the makers whose work I spend the most time with are those that spend their time in ‘the studio’ sitting in hunting stands, sleeping in canoes, driving their old trucks, and coming to understand their environments in ways that I can only dream of. Nature photographers find true miracles—turned over mice, spiders with too many legs, moths with one wing, flowers without petals, deer having fever dreams… I want to find those miracles too, but not just in ‘nature’. Bleached blond kids buying monster energy drinks, house cats swimming near a waterfall, older women watching Herzog movies, a dancing sheep, kids setting fires… There are miracles all over.

SW: Storytelling seems to be both ever present—in the narratives embedded in each picture and even in a hidden text to be discovered by readers of the book—but also resisted, the fragments remaining fluid and mysterious in their interaction, never quite forming a whole. Can you tell me about how you edited What the Rain Might Bring together?

DH: The process of editing and sequencing this book was an intense one. There were upwards of 350 images that I edited from to make the final sequence, so many loved ones, including many of the book’s subjects, helped with the process. I have been spending a lot of my time researching for this project among medieval manuscripts, mainly The Voynich Manuscript and Mandeville’s Travels. These extraordinary objects were very inspiring in figuring out how to bring this object into existence.

I have also been obsessed with the (perhaps overstated) beauty of the number seven in the history of manuscripts. I used this trope pretty heavily in the editing process. WTRMB depicts seven days, it starts and ends at sunrise, and the end of each day is marked by a fold-out sheet of bible paper depicting a moth that came to my studio window every night for a week. Seven as a divine number (seven sisters, seven days of creation, seven steps, seven sins) feels like an important way to enter into the book. I’ve been thinking about this project as an act of divinity—one that both hides and reveals.

This isn’t widely known, but there is not a single word of text in the pages of this book. The publisher and I decided to hide a small zine in the physical object of each book, but you need to destroy the integrity of it to find it—the zine provides a little bit more context for the images.

I really value hiding. And attempts to disappear.