For Chris Leventis, photography is a way to explore the unseen. One part of a greater whole, the artist uses his camera alongside sound recording equipment to create a portal into the many layers of a place. Inspired by the swamps of Florida, Leventis has crafted a unique work process that merges the sonic and the visual to give voice to the spaces in which he submerges himself. Through his engagements with nature, a conversation between many different agents unfolds.

Across his projects, Leventis dissolves photography’s attachment to the ‘decisive’ moment, his approach bending and stretching time to inhabit something deeper; an ambiguous and sensorial sense of time transmitted through frequency and vibration. From his immersion on location to the multiple analog photographic processes he uses, the artist is on a mission to “see the unseen and hear the unheard.”

In this interview for LensCulture, Leventis speaks with Sophie Wright about the accidents that his practice constructs itself upon, his happy places and the different forms his work finds itself in.

Sophie Wright: Your practice is expansive, going beyond the image to incorporate sound and text as well as multiple photographic processes. Can you trace your journey to photography for me?

Chris Leventis: My journey has been one of many tangents and explorations, leading me to see the world in a fragmented way. My first passion was audio. I dreamt of working in a studio, recording bands, and getting lost in the music. It was a dream I let others talk me out of and have always regretted. The universe saw fit to bring it back into my life, albeit in a much different but beautiful way.

Initially, I was self-taught in photography, shooting 35mm film, which led me to medium-format and then to an early adoption of digital. I guess you can say I’ve always had one foot in the analog world and one in the digital. Ultimately, my creative quest led me to pursue a BFA in Digital Art & Technology, where I was thrust into the connection between different mediums. I pursued projects that included audio, animation, video, and photography.

SW: How did that background shape your artistic path?

CL: While immersing myself in complicated and multi-layered commercial projects, I learned to appreciate the in-between. The interstitial moments. When composting for special-fx and motion graphics, the keyframing led me to see the frames that evolved into the final and resulting action–I’m positive this stayed in my subconscious, waiting for the moment to resurface. I jumped from project to project; they were all different and stretched my skillset and imagination in ways I could not even understand.

Ultimately, it was always photography that spoke to me. While all the other mediums had their ‘magic’ moments, there’s nothing like telling a story in a single frame. So, I made some hard decisions and decided to go back to what my gut told me, and I haven’t looked back ever since. That is, until my MFA work when I was introduced to a generative way of honing my process. Making imagery that resonated with me on a primal level led to pursuing historical process printing, book making, and ultimately, back to my initial muse–sound!

SW: The themes of energy and frequency are at the heart of your artwork. Can you elaborate on these ideas and how they shape your relationship to the mediums you work in?

CL: I started seeing an undulating frequency in my work midway through my MFA experience. At first, I wasn’t sure exactly what that meant. I describe it as trying to dial in an old radio or TV, where you almost find the channel, but the interference from neighboring frequencies are interrupting. It took me some time to rectify the emotional response to the cognitive.

I hunted for an understanding, which ultimately led me to reexamine the work of Kandinsky, John Cage, Gerhard Richter, and others. One day, in a meeting with my mentor Elizabeth Greenberg, I blurted out: “There must be DISSONANCE!” Judging by her reaction, I was on to something. I became fascinated by Kandinsky’s methodology of using music as a catalyst for the visual. I realized that music is a plethora of frequencies arranged in a way that forms a voice.

Everything I did involved a disruption, which created dissonance. The dissonance created opportunities that Cage called “chance and accident.” My whole process was a series of accidents that happened because I wasn’t concerned with failure, only the opportunities that chance allowed. The next and perhaps most important revelation was that I was reacting to the energy of different spaces, namely that of the swamp. Its energy converged with mine, and together, we redefined that ‘interstitial’ moment. I tested this hypothesis extensively in the beginning of my practice. Trying to recreate a photograph, I could never achieve the same results.

SW: Across your projects, you create a multi-layered portrait of different places. What kinds of landscapes do you find yourself tuning into and why?

CL: Starting to understand that disruption and, thus, dissonance had a unique energy, I began looking at the spaces I photographed with a magnified intention. The spaces morphed into snapshots of worlds that existed in the past, present, and future. I paid attention to my dreams and started keeping a dream journal, which alerted me to the fact that I dreamt in fragments. Seemingly dissociated instances of events that were somehow connected.

I wandered upon my first swamp by sheer coincidence. It was a small pocket of ‘swamp.’ At the time I was just beginning to focus on fine art and landscape. I was primarily interested in unique trees and the abstraction they provided. It was all new to me and I was fascinated by them and how they became alive. The anthropomorphic nature of trees was beginning to have an effect on how I interpreted the land. Chasing this idea, I quite literally stumbled onto my first swamp. I tripped on a cypress knee (the root system of a cypress tree), and as I recovered and looked around, there was a feeling of peace. My first ‘dichotomy!’ Something about the energy of that space stuck with me and ever since I’ve searched for these ‘pockets.’

I refer to swamps as my happy place because they magnify my connections to the dissociative aspects of my mind. This allows me to conjure spaces inside the shadows and the unseen worlds that intense light creates through refraction; these spaces were invisible to me at first when I used conventional photography techniques. I abandoned what we, as photographers, call the ‘good’ light and started photographing at midday. This accentuated the contrast and pushed those hidden worlds I recognized further to the forefront.

At one point, I was challenged to step away from my initial muse—the swamp—to see how I interpreted other spaces. I took to the coastlines of Florida, Big Sur in California, and my other happy place, the coastline of Maine. I was pleased to see the same mindset and process transferred to different spaces. I’m excited to see how radically different environments and subjects react to this same ‘collision’ of energy, but that is still very much in the generative process. I’m excited to see where it takes the work. Stay tuned!

SW: You work with both sound and image. Why?

CL: I’m so glad you asked that question, which actually was the question that sent me back on the path of exploring audio again. In the beginning stages of a mentorship with photographer Cig Harvey, she asked me: “What would one of your images sound like?” It was a simple question, but when she asked it, my brain was lit on fire! Here was a chance to bring my love of audio back into my life and process. Of course, my images had a voice! But what were they saying? How would I find out? All these questions within questions formed a framework that began my exploration.

SW: How did this revelation translate into action?

CL: I started with field recordings to see what the inherent sound of the swamps sounded like outside of the space. I heard many sounds, and it was interesting, but it wasn’t enough; it was what was expected. I needed my sound practice to mirror my photo practice; one of the in-between, the unheard, the merging of time—what did that voice sound like?

I researched for what seemed forever and came upon the practice of ‘plugging in’ to plants and using their electrical energy to create music. Using that technology, I converted their bioelectrical energy into MIDI notation, which triggered conventional musical sounds. Again, that was more interesting than just field recordings, but it still didn’t feel authentic enough. Once again, I researched and came upon the practice of modular synthesis. It used energy in the form of voltage to create sound, and more importantly, it could be unpredictable and never produced the same results twice. This felt like the way to finding that authentic voice I was searching for!

I built a custom instrument using modules that allowed for more precise reading and creative interpretation of said energy. I took this into the swamp, and together, we started creating music. Over time, the swamp and I composed songs unique to each space I photographed. For me, harnessing the energy of the swamp that gave my images a voice was the last piece of the puzzle that allowed me to approach my now interdisciplinary practice in an honest and authentic way.

SW: The way you describe your projects is almost as if you’re in collaboration with the landscape and its inhabitants. How do you see the relationship between you and the place you’re documenting?

CL: The swamp amplifies my emotional state because of the many stimuli it offers. With its biodiversity, it has this archaic field of palpable energy, which adds to the depth of the emotional response. It’s a partnership. Together, with our convergence of energy, I feel I’m able to show worlds that exist only in that instant I press the shutter. This is exciting and fascinating to me. I describe it as a collision, resulting in the final, unique image.

SW: I can feel sound and vibration on the surface of your photographs, while your soundscapes are rather cinematic. How does sound inform your visual aesthetic and vice versa?

CL: Vibration makes sound. Frequency is vibration. Everything is connected. My images can be looked at as a musical score of the in-between. At least that’s one way I imagine them. The shadows are the rhythmic elements and the light is the harmony. Their interaction is essential in visual and sonic interaction, and they inform each other. I think about these interactions, whether the visuals or the music, when making the work.

SW: Can you talk me through your workflow once you’re ‘on location?’

CL: My workflow is intuitive and ritualistic, and I always work alone. When specifically photographing, I always listen to music from a curated playlist. While it might seem reckless to wander a swamp alone without the sense of sound, it’s a critical element and well worth the risk. The music frees my mind from trivial thoughts, and allows me to connect to the landscape in a spiritual way. I move with the music which is paramount as my process behind the camera is akin to a dance.

All my images are long exposures ranging from five minutes all the way to an hour. For my current series, I’ve built a hybrid camera consisting of a medium format Fuji camera on the backend and a Cambo bellows on the front end. I favor older large-format lenses, specifically uncoated versions—they allow for aberrations, flares, and other disruptions. Everything is in motion, my tripod and various movements from my bellows. It’s an orchestrated dance, and I get lost in it. It took a long time to hone it; a process born from chance and accident, but I paid attention to those accidents, and it’s made all the difference.

Usually, I’ll walk in from the trail and just look and feel the space. When something feels right, I put my tripod down and begin. Once the tripod is set, I don’t move it; that would mean second-guessing my intuition. Lastly, I never look at my images immediately. I usually wait at least two weeks, if not more. I’ve learned that when I wait that long before I begin post-production, I make better choices on which images to work on. I think it’s because I have distanced myself from the experience of making, and I can make decisions based on emotional responses to ‘fresh’ images. I also listen to the same playlist while making those decisions and during the post-production process. You see, music is an integral part of my whole artistic process.

SW: You mix digital and analog technology, can you talk about your preferred processes? Why are historical photographic processes the right container for your ideas?

CL: I never crop my images, and the only post-production that I allow myself is dodging and burning, much like in the darkroom. While I don’t look down on composting and other creative methods using the computer, this work must come from the conduit that is formed between the space and the lens. It goes back to the idea of chance and accident; this is paramount.

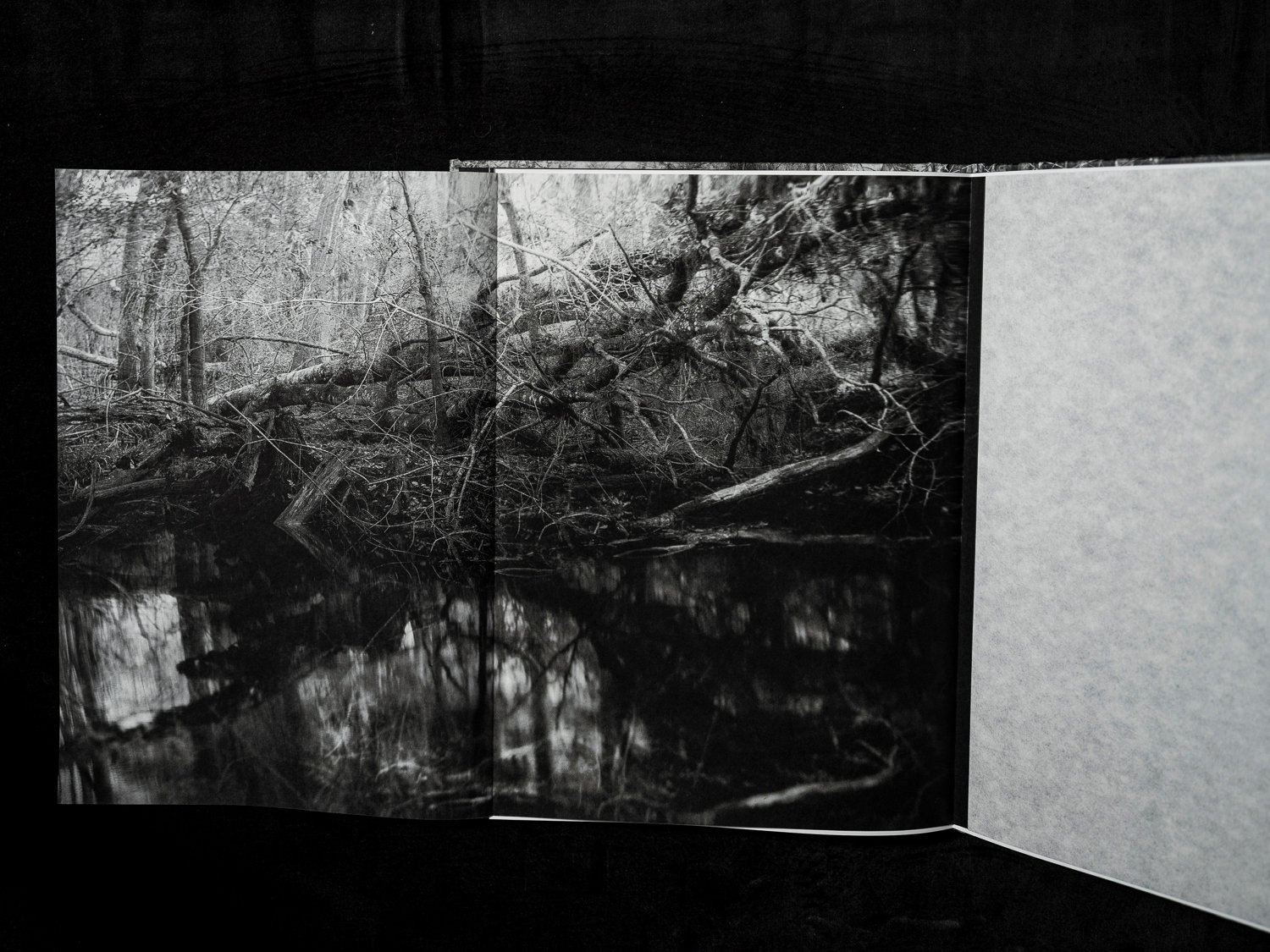

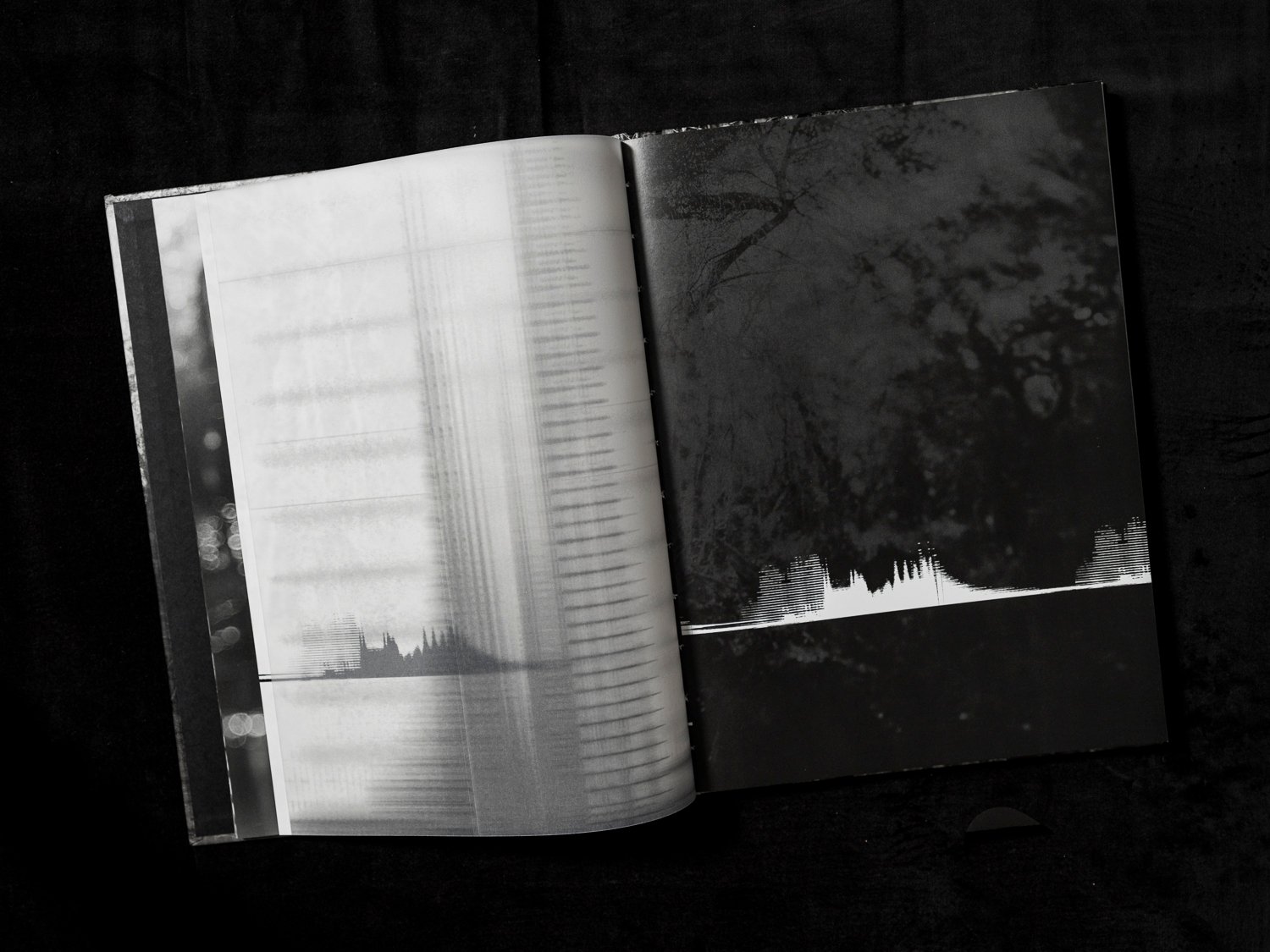

I choose methods that allow for disruption. Silver Gelatin, Platinum, and the Gravure process allow opportunities for further expression inherent in the work: time and dissonance. Because I use a digital back, I must create a digital negative; from there, the process becomes fully analog. All of the printing processes I use importantly demand evidence of the hand through interaction with the chosen medium.

There’s a beauty in the individual print that these processes produce. While a master printer can come close to identical prints, I prefer the beauty of subtle variations. Whether it’s the way platinum and palladium ratios are used, or how ink is laid down and wiped off in the gravure method, or the type of developer one uses with silver gelatin, there is always an opportunity for variation among each print. I find that beautiful.

SW: Sound + image almost = cinema. Is it important for you to work outside of the realm of moving image?

CL: I’m not against the idea of video; I have plans to incorporate video into my work at some point. Specifically for this series, because of the complexity of the image and the sound, I prefer to allow the viewer the space and opportunity to make connections between the image and their emotional reaction without having their brain rectify what the movement means in conjunction with the audio cues.

When paired with the moving image, sound becomes something different; it’s not better or worse, just different. You see, there’s the same collision of energy that I use to make the work that happens when someone experiences my images. Allowing yourself to wander through them amplifies the sound and will enable it to guide the emotional response. The result is the same type of convergence I use in the field. This is what is most important to me.

SW: Your work seems to find form in many ways. Do you ever encounter challenges when faced with the boundaries of each medium? Or for example, how your work sits in the online space?

CL: The online space is challenging to navigate. Of course, showing an image on a website can and does have an impact. It has to. If the image itself didn’t affect the viewer, then I view it as white noise; it is there but it remains utilitarian. However, each medium offers a unique approach to expressing the work. Adding sound is relatively simple in this arena, but I don’t think it is as impactful because I now have to ask the person to listen for a prescribed amount of time. This is difficult to navigate in the online space; it takes commitment from the viewer, and we have no control over that, which can diminish the experience. Having said that, I think an online space for the work is essential.

I love books! A remarkable thing happens when someone turns a page and is presented with imagery in a way that it becomes intimate. You can hold it in your hand and feel the page. With the added dimension of text, there’s an opportunity to elevate it further. The boundary here is the inclusion of the sound component. QR codes are a simple, but in my opinion, an inelegant way to approach it. I don’t have an answer to this boundary yet, but I’m working on it.

SW: And how about more embodied formats of presentation?

C: Showing the work in a gallery or museum is essential. How you sequence it, the print size, the type of frame, and the actual printing method all merge as a different experience. It’s not better or worse, it’s a different set of considerations, but in my opinion, a satisfying way to present a body of work. I’ve endeavored to bring sound into my shows to allow the viewer total immersion. This is still evolving, but I’m excited to see where I can take it. I’m currently planning a solo show in Tampa, Florida where sound will be an equal player in the museum experience.

The performance aspect of my process is special to me. I now have the opportunity to add the audience’s energy to mine. The nature of modular synthesis is such that no performance is ever the same. This cuts through and amplifies the imagery projected behind me during the show. Like the imagery, chance and accident truly shine and take me to unique places every time; bringing the swamp and its energy to an indoor space has a surreal dichotomy.

Editor’s note: You can check out videos of Chris’ live performances here.