What do we see when we straddle the border of being both here and there, simultaneously belonging and remaining a stranger? What is it that stands out or catches the eye? Bruno Quinquet, born and raised in France, became a photographer in Japan, where he completed his photographic studies. “In certain regards, I feel very remote from my roots. I was not a photographer in France; I became one in Japan,” he says. “Sometimes I feel that I will never be a full part of that community but I’m not part of any other community.” From this in-between position, Quinquet has created a body of work that captures the Japanese landscape with incisive, clever, and considered brushstrokes.

In his ongoing series YUBIN, Quinquet has assumed the role of postman walking the streets of Japan, ward by ward, photographing postboxes. He plans to walk all 23 wards—the city’s separate districts—of Tokyo, noting the enormity of the task. “Last year, I walked all the streets of Sumida ward in 46 walks between October 3rd and December 8th,” he explains. The title YUBIN comes from a stylized katakana character テ (te) which was the first syllable of the name of the Ministry of Communications ((逓信省 teishinsho) at the time of the postal service’s founding in 1887.

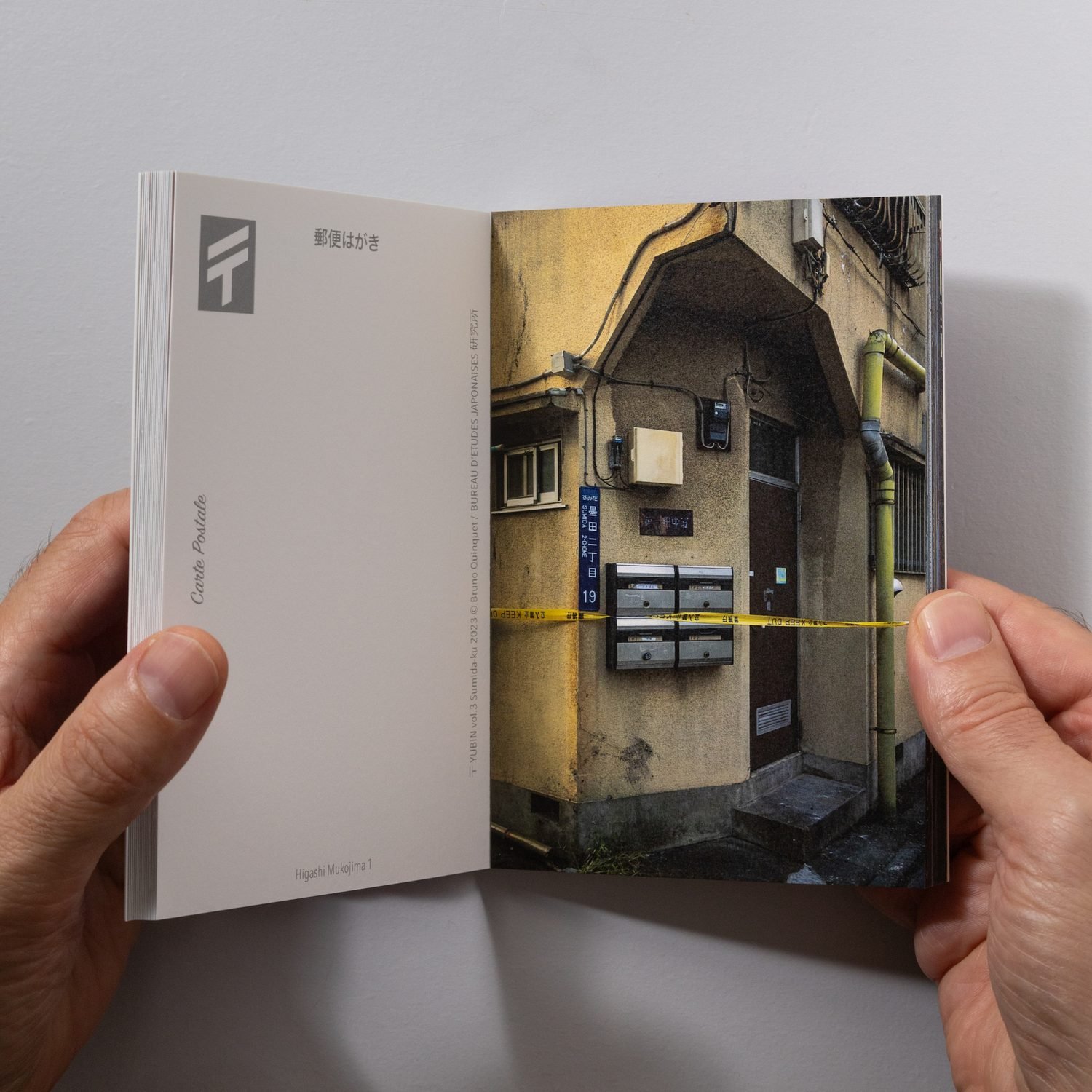

A postbox might seem the epitome of banality but through Quinquet’s eye, we see a wider world, at times perfectly neat and minimal, at other moments jerry-rigged and somewhat absurd. His lens finds a cherry blossom branch emerging from a bare stump, elsewhere a postbox is balanced precariously on a stack of bricks. His interest lies in seeing the city through the eyes of others; creating parameters for his projects, he assumes a role and performs the actions of a postman, a corporate culture investigator, or an ill-informed botanical researcher, allowing the roles’ daily routine to guide his image making.

Quinquet works under the moniker ‘Bureau d’Etudes Japonaises.’ The name, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, reflects the important role that institutions and companies play in Japanese work culture. He explains how in Japan “it is better to be a part of something than by yourself, if not a company then a lab or an association. So I made up a name which the French think is kind of a joke and the Japanese see as serious. It has a surreal touch to it,” he says, also pointing out that some artists claim to be interested in the overlooked, the things people don’t pay attention to. “But the difference is that I am truly interested in these things not because they are overlooked, but rather because they are incredibly important elements of the city.”

The key to Quinquet’s work is how elegantly his concepts are given shape. YUBIN began as an idea of making postcards from post boxes. Comprising three volumes, YUBIN is presented as a book, shipped in a postage-stamped box specifically designed for the project. Each volume includes 36 photographs which are all individually detachable, ready to be sent back out through the postal service if desired. Volume three includes a postcard for the viewer to send back as well as an unpublished one which the artist will send in return, a circle with which to extend the project.

His earlier work The Salaryman Project Business Schedule found its form in a printed business agenda, each week capturing an image of a Tokyo salaryman evading the camera. These businessmen, an ever-present facet of local culture, remain just out of clear sight, their features lost in the fog of a window, disappearing around corners, obscured by flowering branches. The photographs are an inventive mixture; formally sharp and at points humorous in their composition, while managing to capture a certain strange pathos of the salaryman—alone, mysterious, and elusive. “When I started photographing I thought that the photo had to be composed, that you had to be aware of its composition. So my first images were very formal. I then tried to shift from that and accepted that I liked this approach too. Sometimes I do it, sometimes I don’t.”

Something that is successfully simple at first glance often entails a fine balancing act between multiple elements. Is the idea strong? Does the concept work with the execution? But more importantly, is the work alive? What may seem at first glance like a clever idea is elevated by Quinquet’s discipline and devotion—a process followed almost obsessively to its endpoint, each decision reaching out and back, referencing art history, the culture of work, and tangible forms.

Photography is full of specific formats and trends that bubble up. A typological framework is one format that is a timeless organizational tool. Yet Quinquet’s YUBIN, for all its systematic form, does not take the form of tried and true typology. Instead, he breathes life into his conceptual framework by allowing it to evolve with time, to incorporate seasons, to introduce an exchange. Recently there has been renewed interest in the flaneur, flitting across the city on a wandering dérive, allowing themselves to be drawn in by the encounters and attractions they find.

But what of the sharp eye darting around the grid, persistently walking block by block, finding surprises within the ordered borders of Tokyo’s wards? Quinquet calls this systematic approach liberating. In freeing himself from certain decision making he allows himself to take on the perspective of someone else. “It’s a work that looks from the perspective of someone else; an imaginary person who embodies a postman, working in the area for the first time. It’s not a rule, but rather a point of view.”

What may seem like a rule-bound, rigid approach is thus surprisingly playful in Quinquet’s hands. Across his projects we find a photographer exploring his surroundings with wit and understated flair, assuming personas, and ultimately thriving in the in-between.