Against a bright blue sky, stands a shingled house in shades of gray. Obscured by brittle winter vines it looks as if someone has tried to scribble it out—a Cy Twombly at the end of a rural lane. Is it a photograph of nature left to its own devices or an interesting study in form? The answer is something much more intriguing, one well suited to a place rich with dynamic history. The photograph was taken in Martha’s Vineyard, an island off the coast of Massachusetts and is titled Where He was Hidden. So who was this mysterious ‘He’ and how does he fit into this story?

His name was Randall Burton and in 1854 he stowed away on a boat to escape enslavement in the South. Upon discovery, he eluded capture and made it to the shores of Martha’s Vineyard. At the time, The Fugitive Slave Law of 1851 was enforced across the United States. Any person who was caught in the North could be sent back to the South. On the run across the island, he was given shelter by a Wampanoag woman named Beulah Vanderhoop. The story was covered by the day’s papers and passed down through oral history. Vanderhoop managed to get Burton to the mainland and he eventually made it to Canada.

For Austin Bryant, the story of Burton and Vanderhoop was a natural starting point for his project, Where They Still Remain. The Wampanoag of Martha’s Vineyard are part of an Indigenous group of the Northeast Woodlands. Prior to colonization they were believed to have had a population of upwards of 40,000 people. There are only around 4,500 enrolled members today. Burton’s story struck a chord with the photographer.

“It was the dynamic of these two communities coming together. I am the black son of a white mother. I am biracial and I’ve always been interested in the intersection of cultures. This is a story of the intersection of these two discriminated groups. And I would say, the two groups that are the foundation of discrimination in the United States. One group was here and they were displaced, the other group was brought here in chains and used as labor. I was fascinated with them coming together at this point,” he explains.

This convergence is deeply ingrained in the island’s history. Bryant grew up spending summers on the island, noting, “I have a deep connection to the island. I could be considered as part of the extended legacy of African Americans on the island. Black Americans have been going to Martha’s Vineyard since enslavement ended, and often before that they were sailors on whaling ships. They married into the Wampanoag tribe. So there’s a dynamic in this history of this legacy. We or they have been there since emancipation.”

Bryant learned about Burton after having read of the dedication of a trail on the island. A natural researcher, he began looking into archives and speaking to members of historical societies and Wampanoag members. The Wampanoag’s cultural resource officer, tasked with preserving tribal heritage, connected him to another community member focused on preserving the dying Wampanoag language. Each meeting opened another avenue of exploration.

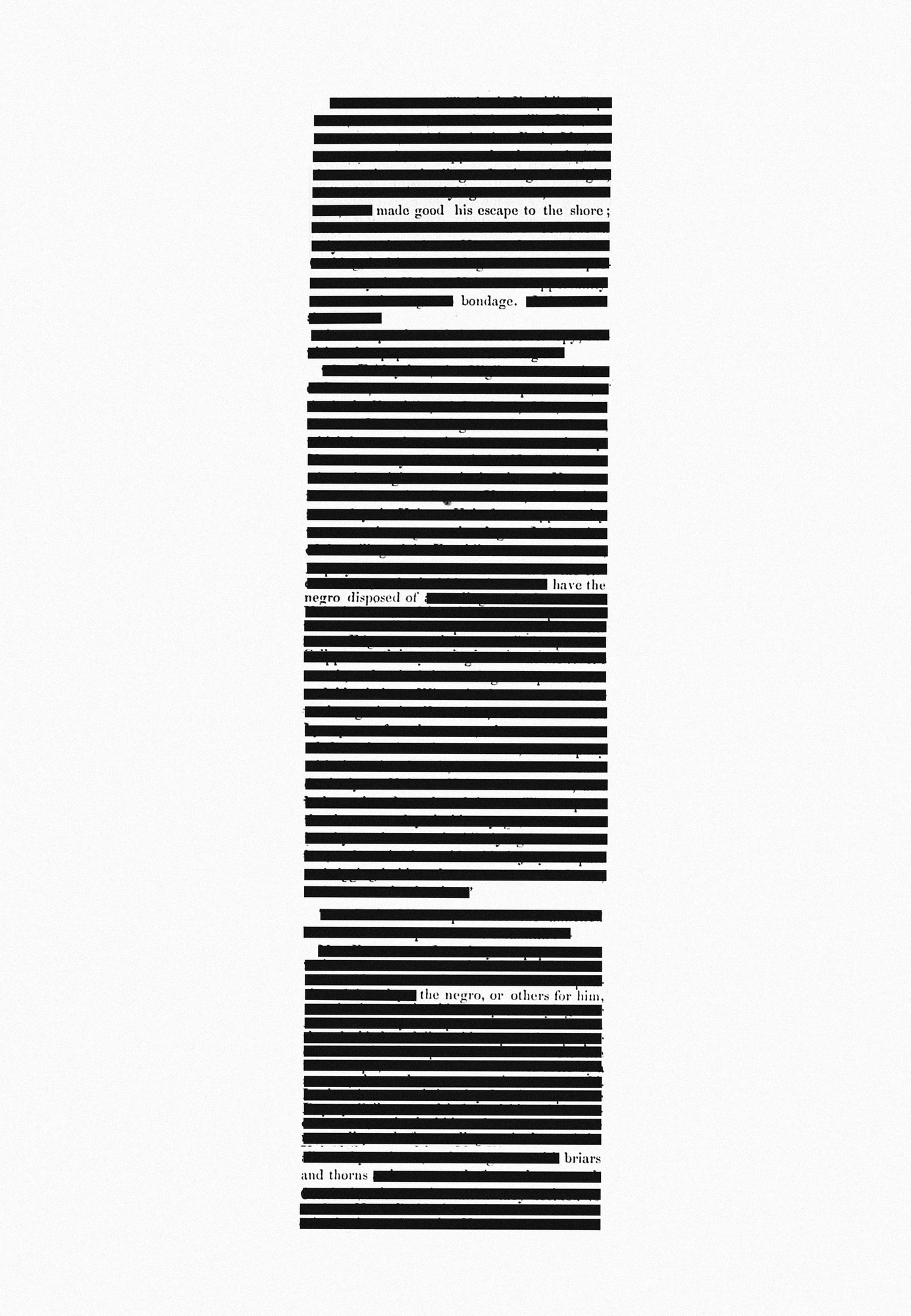

He made portraits of locals, captured the landscapes of myths, and documented ceremonies. Each photograph acts as a puzzle piece, filling in an often overlooked, and in some cases even erased, story. As he continued working, the series became broader, extending beyond Burton and onto the history and present-day of the island’s Black and Wampanoag community. The text within the work is radically stripped back, four heavily redacted newspaper articles act as breaks or chapters. “I was so focused on making people understand this story, and how amazing it was to me. But I realized restricting the amount of language broadened its impact,” Bryant explains.

Where one could write a whole history, Bryant has chosen to visualize a world, immersing himself in the island’s localities and lore. The color red, suffusing a nighttime scene or enriching the soil, appears throughout the work, referencing the creation myth of the Wampanoag and a connection to the earth. Amidst scenes of the island’s wide open spaces, there are images from the past, sourced from various public access archives. Bryant was amazed by a series of 8x10 glass plate negatives, featuring residents, most often with no labels or jarringly dismissive ones, a nameless young boy with the caption Black.

Referring to the small boxes that these collections fit into, he observes: “It’s like their history is not deemed important enough to be carried on. There is a dynamic of people not seeing these images of those communities ever or often at all.” Describing an image of an Indigenous couple, Bryant observes, “They’re an older couple, the woman sitting is looking off and the man is looking down the camera, surrounded by this sea of white people, white women mostly. The feeling I would get from an image like that is ‘Oh that is the reality of it, restricted to this place, rounded in a sea of whiteness.’”

This proof of existence is poignant, and as his own photographs demonstrate, ongoing. With each person and place, a fuller, more vibrant history is cemented in the record. Finding Vanderhoop’s house was a moment of kismet; a full circle moment, connecting past and present. “A historian brought me to the house,” he recalls. “It was down a dirt road that I had driven by countless times. It was hiding in plain sight, which I think is an apt description for the types of histories I’m looking at. It was there all along, owned by a different family, neglected. It has been open to the elements for probably four decades. It was a time capsule walking in.” Image by image, Bryant has made the unseen seen, stopping to follow paths others may have missed, sketching in the details of communities that not only remain but persist.

Editor’s note: Austin Bryant’s exhibition Where They Still Remain is on view at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum until June 29 2025. The project was shortlisted for LensCulture’s New Visions Award, in the Storytelling category this year.