Photographer Arrayah Loynd has had a long-standing routine in the small town she has lived in for almost 20 years. Every Wednesday she would take a walk down to the charity shop, looking through items and chatting with the women there. After Australia went into lockdown at the start of the pandemic, her routine switched. Walking to get a coffee one day, she ran into two women who began to speak to her as if they knew her.

“Normally I think I can mask it but, because I was so out of practice from being isolated, I had a look of panic on my face. And then it was so lovely. They said, ‘Oh, you know, from the charity shop.’ And I had a sigh of relief because I didn’t have to try and work out who they were. But it just struck me, how could that have happened? I see these women every week, but they were out of context, only 100 meters or so out of context,” she recalls.

The following day she stumbled upon a television program that would provide an answer. The documentary featured an artist who was photographing ‘super-recognizers’ and their opposites; people with prosopagnosia, also known as face blindness. Those who have prosopagnosia cannot recognize familiar faces, often relying on context to place people. All of a sudden, Loynd had a name for something that had plagued her throughout her life.

Inspiration in art comes in many forms—a snippet of conversation overheard, a memory, a piece of music, a news story, or a past to be mined and explored. Sometimes it is a series of things that build over time and at other times it is a comet shooting through the sky: a moment that forces a new understanding of the world. For Loynd, putting a name to her experience opened the creative floodgates.

So associated is photography with the concept of remembering—“pics or it didn’t happen”—that it has lent itself to the phrase ‘photographic memory’ meaning the ability to visualize an image from memory so precisely that you might as well have the photo in your hand. But what if your photographic memory is missing?

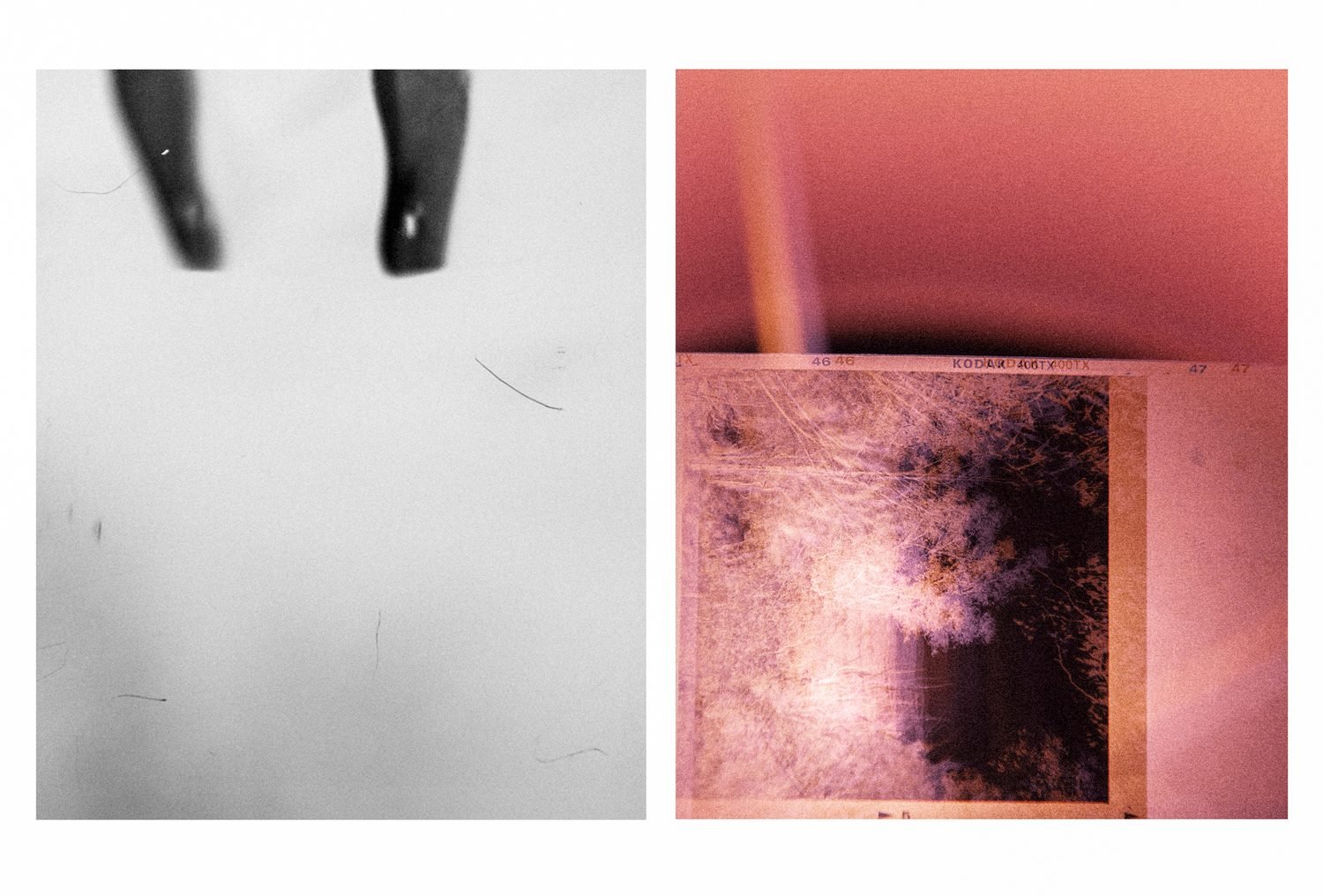

After a conversation with a friend who was working with analog photography, Loynd decided to revisit her old negatives. “Sparks just went off in my mind. And I thought, this is what I’m going to do and I’m now ready to do it,” she remembers. “The negatives were all of the duds, the ones that you throw out. They were all blurred and either under or overexposed; there were ones that you couldn’t make images out of.” These scraps of images and moments would become the building blocks of Loynd’s project. “People always talk about photographic memory. But for me, I don’t have that. I have the opposite of that with prosopagnosia, object impermanence and my neurodivergent diagnosis. It’s a massive mess inside my head, and nothing is linear, nothing is stuck. My memory is all jumbled up.”

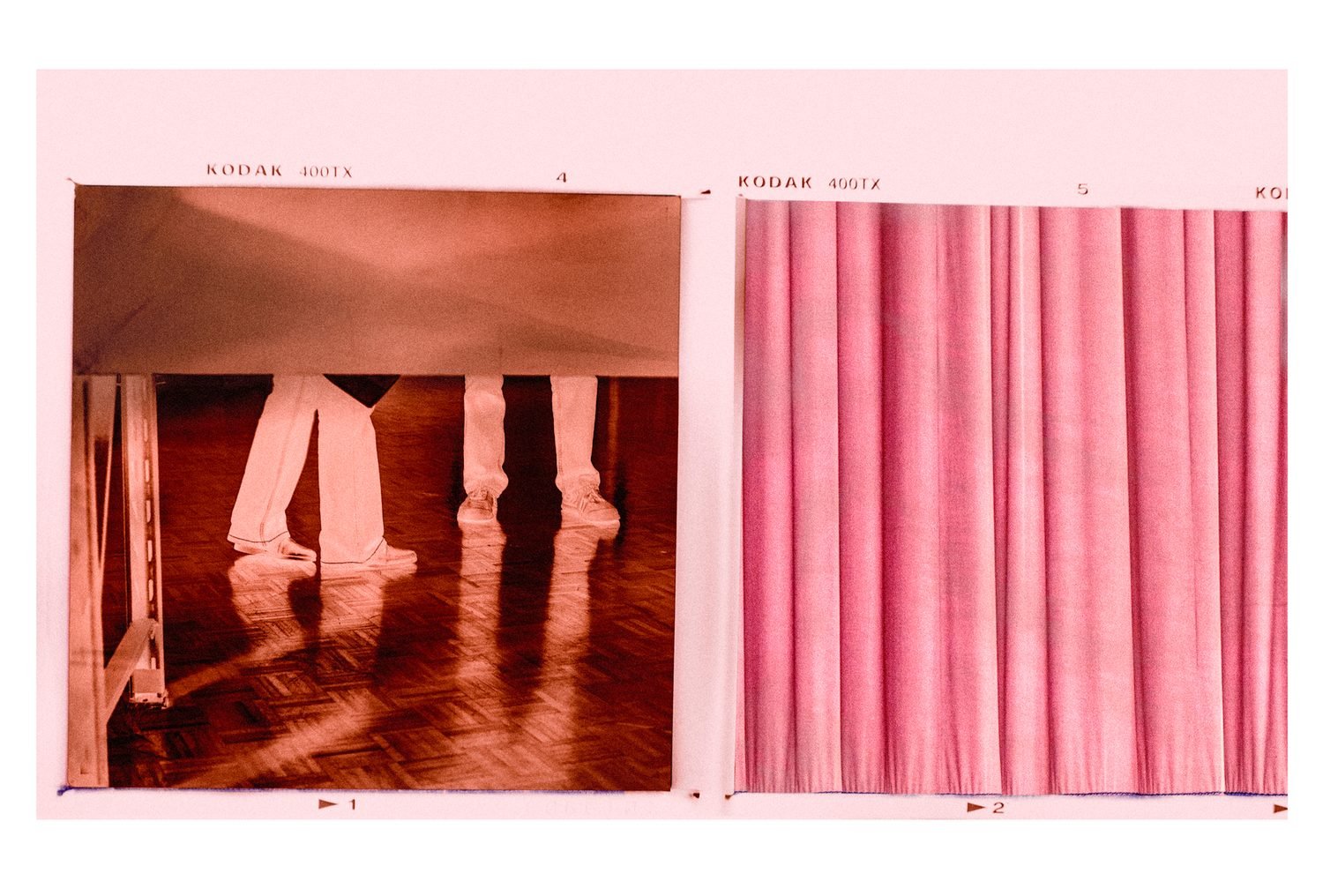

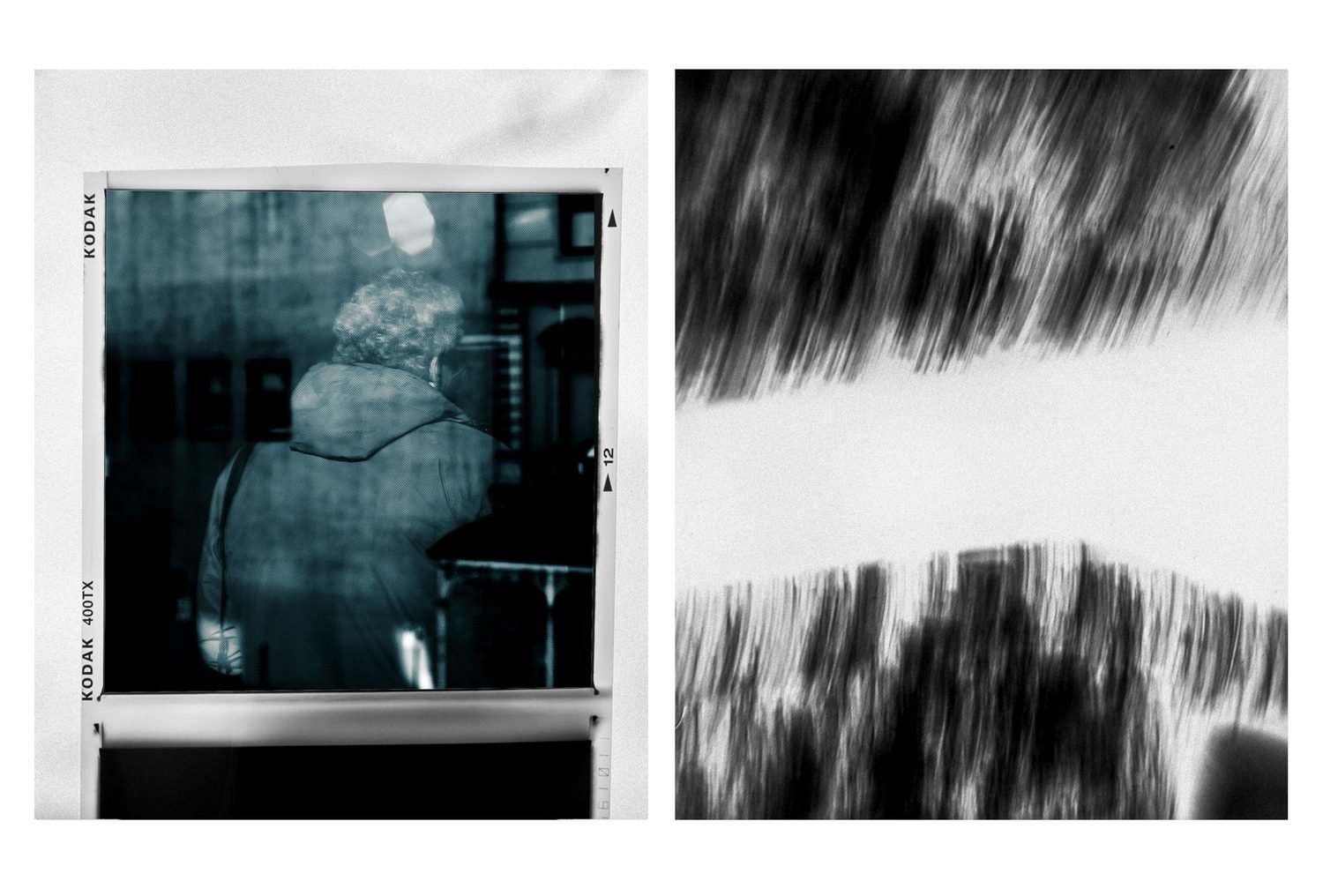

It is just this “jumble” that makes the work so alluring. Loynd’s images walk a tightrope between stark simplicity and rich detail, teeming with texture and gorgeous washes of bold colors. Moving through the photographs, one is pushed between silence and noise. There is a sense of memories rising to the surface and meeting moments in the present. The photographs flash across one’s eyes and rove the mind—a houndstooth patterned coat, an outstretched leg, a cropped hand, a flurry of lights that read like radioactive fireflies.

“It feels like the purest expression of what it is like to be in my mind,” she explains. And then you were gone. When read aloud, the project’s title also captures this feeling, prompting the physical sensation of “blink and you miss it” or the quick head-turn that signals momentary puzzlement. Who or what was that? Where did it go?

Loynd’s photographs are presented as diptychs, a format she has used in the past for how the images talk to each other. She began the work by taking photos of herself holding the negatives up to different light sources, whether it was in front of a TV, up to the sky, or against trees.

“I work obsessively and quite fast when I’m hooked on an idea. A lot of those images are very straightforward apart from inclusions of color. With others, I’ve laid over a lot of archival material to bring in some portraits or some bodies, but the majority of the images are the actual negatives,” she muses. “They look highly processed, but they’re not. I see the world in almost an electrified intense way and I love color. I just go full tilt and create it. It’s a mechanism for processing the things that I can’t process internally.”

For the photographer, developing a greater clarity on how and why she sees the world as she does has been creatively liberating. “It’s allowed me to be honest. Because every time I put work out that’s quite vulnerable, I can mask less and less because it’s out there. I don’t have to explain all the time,” Loynd reflects. “People just have to look at my work and read my words. There’s a greater understanding of myself, but also for the people in my life. It’s as if a weight is lifted every time you explain something about yourself like this. When I started turning the camera on myself, I just let go of any of those feelings of inadequacy because no one could tell me anything was wrong, because it was about me.”

In pouring her truest self into the series, Loynd has created a body of work that though it may be built out of past imagery, has the overwhelming effect of shimmering, intuitive immediacy.