Majuli, the world’s largest river island located in India, is slowly disappearing under the waters of the River Brahmaputra. There, daily life is indelibly shaped by the climate catastrophe. Flood Me, I’ll Be Here is the outcome of András Zoltai’s five year engagement with its place and people. Through witnessing the intimate relationship communities living on Majuli had with the land and water, Zoltai’s perspective evolved from what might have become a destruction-led climate-related narrative to a quieter one. The images that make up this photobook document continuity rather than fracture, as the photographer focuses on resilience—on the “connection people have with the river, the water, and the land that nurtures them.”

Unfolding through a series of images, diary fragments and an original text by Indian artist Davadeep Gupta, Flood Me, I’ll Be Here charts the photographer’s own personal journey as well as the changes happening on the island. Working on the project prompted a profound shift in his understanding of our shifting environment—and how to survive it. His time in India triggered a reflection on his own experience growing up next to the Tisza river in his native Hungary in relation to that of the island’s inhabitants, leading to a separate body of work made in his “own backyard” on the topic of water and how our relationship is at risk.

In this interview for LensCulture, Zoltai speaks to Sophie Wright about “chasing water,” his shifting perspectives on the climate crisis and how to document the experiences that arise from it and the interrelated threads of life by the water in India and Hungary.

Sophie Wright: Tell me about your journey to photography and what has kept you there. What are the key thoughts and feelings that drive your work?

András Zoltai: I’ve been working in photography for 10 years now. For those who know me well, this isn’t just a profession; it’s a way of life. Of course, the journey has had its challenges. Feedback isn’t always immediate, and there are many days when it feels like I missed capturing that one image or story—especially when working on long-term projects. But that’s okay, because this craft continues to elevate me to intellectual and emotional heights that still surprise me, even after a decade.

In many ways, my journey into documentary photography has been spontaneous and impulsive, just like my personality. I’ve always tried to follow my instincts. It might sound like a cliché, but I simply focused on stories that deeply interested me for one reason or another—stories through which I could experience the process of photography as one of the purest forms of connecting to the world.

A photograph may be taken in a fraction of a second, but everything leading up to it—the fieldwork, the people I meet, the conversations I have, the countless kilometers I travel—feels even more meaningful. I believe it’s these moments that gradually make me a more empathetic and grounded person. On the harder days, I draw strength from them. I may never fully understand the world, but I try to share it as I see it.

SW: Water is the source of two of your works—one made in your home country of Hungary and this one, made in India. How did water become your subject? What is your personal relationship to it and how did it evolve?

AZ: First of all, my childhood and memories were my biggest inspiration for chasing water. We lived just a 10-minute bike ride from the banks of the Tisza River in Hungary. We often went there as a family, and we had a summer house right on the riverbank. As a teenager, I spent a lot of time alone at that holiday house—fishing, inviting friends over, and simply being by the water. Szentes, the town where I was born and raised, is also famous for its thermal baths. I actually learned to swim in a thermal pool. Even now, I still go to the thermal baths in Budapest every Monday morning—it’s a bit of an obsession, but also a part of our culture.

For a long time, I didn’t really reflect on those memories or my relationship with water. It was actually in India that I realized how important water was to me and that I should do something with that connection. While photographing communities living along the banks of the Brahmaputra, I was involuntarily and unexpectedly triggered by my own memories. I started to compare the two realities. It was incredibly inspiring to see how deeply connected the Assamese people are to the river. That made me start questioning the situation in Hungary. Do we still have that same connection to water or is it disappearing? How is climate change affecting us and our waters, and in what ways?

At that time, the pandemic was already in full swing. After completing my field trips in India, I felt a strong desire to start a photo series in my own ‘backyard.’ It became clear that I would focus on the human–water relationship.

SW: Do the two projects flow into each other?

AZ: Once I was in Majuli, photographing two men pumping water from a pond to irrigate their rice fields because the monsoon hadn’t arrived on time. As I watched them, I thought to myself: this image could have easily been taken in Hungary. A key moment in my practice was realizing that I had to go far away in order to understand that I needed to start telling a similar story at home in Hungary—because it deeply matters to me.

That’s when I truly grasped the scale of the problem and began to understand my role and potential impact as a photographer. That distance helped me see that I could apply everything I had learned abroad to my homeland: to raise awareness, educate others, and potentially influence water policy in Hungary.

Back home, all my local knowledge comes together. There are no language barriers, and I was born and raised near the Tisza River. I share the same cultural heritage, which allows me to interpret the issue from a unique and personal perspective. Since the project’s locations largely overlap with the landscape of my childhood, I had excellent access to the communities involved—even to remote and lesser-known areas. On top of that, I had a strong local network to rely on for practical support, logistics, and navigating any challenges that came up. So the two projects had a strong influence on one another.

SW: How did you first find your way to the River Brahmaputra in India, the body of water that courses through Flood Me, I’ll Be Here back in 2020? What first struck you about Majuli island?

AZ: I first heard about Majuli from a very good friend who visited the island about 10 years ago. What really stuck with me was when he said that life on this island still looks the way it might have looked in the floodplains of Hungary centuries ago. That was the trigger. I had long planned to travel to Northeast India, and I managed to make the trip just before the pandemic.

When I first stepped onto its shore, childhood memories of floodplains came flooding back to me. I was deeply moved by the close connection to the river and the water. It took some time for me to understand the dynamics of life there and the problems faced by the people living on the island. At that point, I wasn’t thinking in terms of such a large (book) project.

After I returned home, I developed the narrative further and began to seriously work on continuing the project. Unfortunately, the pandemic slowed things down, but perhaps that buffer period was exactly what I needed to better understand what I actually wanted to do. At first, I had a classic climate narrative in my head—that this island is disappearing and everyone is a victim. After my second trip, I realized that no matter how hard I tried to tell that story, it simply wasn’t the case. I started to focus on human resilience and connection instead of purely on environmental crisis. Instead of sensational images, I became drawn to the quieter, more peaceful moments of everyday life—the continuity of living, the connection people have with the river, the water, and the land that nurtures them.

SW: Can you tell me a bit more about the island and the people you met there?

AZ: Over the past decades, the island of Majuli has shrunk to a third of its original size due to intensifying soil erosion. The global environmental changes of our time have not spared this region either: the monsoons no longer arrive as they once did, and the floods have become more unpredictable. As infrastructure has developed, embankments and sandbags now line the riverbanks, trying to hold back the advancing waters. At first glance, it seems that Majuli’s ecosystem is also being disrupted—another chapter in the unfolding story of climate change disasters.

Nevertheless, the resilience, adaptability, and quiet perseverance I witnessed on the island became deeply symbolic. The longer I stayed, the more I realised that my journey was intertwined with the profound physical, social, and spiritual reverence the local communities hold for the river and its sacred waters. I tried to spend as much time as possible with the people of Majuli—understanding their motivations, and sensing both the struggles and the joys of their daily lives. From farmers to buffalo herders, from fishermen to potters, they all shared a deep, intimate bond with their environment and the river that sustains it.

I mostly photographed two ethnic groups: the indigenous Mishing tribe and the Assamese people. While their lifestyles differ somewhat, both communities share a deep connection to the river. It was fascinating to witness their respect for it and the remarkable level of adaptation in their daily lives. On my first trip in 2020, I traveled everywhere by bicycle. The roads were still unpaved, there were fewer cars, and concrete hadn’t yet reshaped the villages. Over the five years, the infrastructure is perhaps what changed the most. I was present at the foundation ceremony of a planned five-kilometer bridge in 2021—and on my most recent visit, I saw the giant, half-finished concrete pillars rising from the water, promising yet another massive shift in the island’s future. Symbolically, this is where I choose to end my new photobook, marking the beginning of the next chapter in Majuli’s unfolding story.

SW: You mention that the perspective between locals and outsiders on water-related problems and how they played out in daily life was unexpected. Can you elaborate on this observation?

AZ: When I first saw the sandbags and witnessed the destructive power of soil erosion, the narrative that immediately formed in my mind was one of disappearance—a story focused on the island vanishing, on people being forced to leave their homes and search for new places to live. What was unexpected was how differently the locals responded to these challenges compared to how we might.

Many chose to stay—even in the most critical areas. Instead of abandoning the island, they adapted: moving their houses to new locations, but not leaving Majuli behind. Their perspective doesn’t begin with destruction—it centers on the power of water and the deep respect they hold for it. They’ve accepted that the river always gives and takes. This kind of acceptance is something that’s missing from our own culture, where we often try to control nature by force. I was really struck by this respectful, coexistence-based attitude toward one of our most vital natural forces. I got the sense that, in the minds of the people living there, the concept of a water-related ‘problem’ simply doesn’t exist—it’s almost unimaginable.

Of course, that doesn’t mean they aren’t taking measures to protect the island in their own way. You can see how much effort they take to protect, but they do it together as a community. And the daily lives of the people aren’t shaped by a narrative of victimhood; they are rooted in a narrative of coexistence. As an outsider, it took me some time to realize this—and it completely shifted the way I approached what kind of images I was looking for.

SW: Your images deal with things that are difficult to capture—slow but powerful shifts in the environment that contribute to the water crisis and its effect on the surrounding communities. How did you arrive at a visual language that speaks of the many layers you’re dealing with here and how did it unfold over time?

AZ: I had to reinvent myself through photography day-by-day in such a distant place—and in fact, that’s one of the reasons I keep doing visual storytelling: to look at the world a little differently each time, to observe from new perspectives, to rediscover wonder. The more you return to a place, the less you feel you truly know it, because you’re constantly confronted with new stories and lives that you can get lost in. I love this feeling. During my travels, I kept trying to clarify what my personal motivation was in Majuli—why I kept going back so many times, and why I felt such a strong need to be there.

If I look back, I can see how much my visual language has changed. I wanted to portray the continuity of time, despite all the destruction through still images that actually stop time in its tracks. On Majuli, I felt that I grew into the task of expressing emotional depth in my images. I left behind facts and rationality; I didn’t focus on when the rains and flood would come or where the so-called disaster zones were. Instead, I let myself drift with the events and everyday little moments.

That shift brought a major transformation in how and when I choose to press the shutter, and what I pay attention to when I’m seeking images. This approach gave me a kind of creative freedom that made me feel like I was soaring—as if I could be flooded by anything, and still, I would be here. That feeling is what motivated me to make my final journey before the book, which marks the closing of this five-year chapter and the beginning of a new one, as I now fully turn my attention toward my Hungarian project.

SW: Can you tell me something about the title “Flood Me, I’ll Be Here”?

AZ: The title can be read in two ways, reflecting the interrelatedness of my experience and those I was photographing. On one hand, it speaks to the resilience and perseverance of the people living there. They’re not afraid of the flood or the power of water—they will hold endurance and stay until the very last moment, no matter what happens.

But later, I realized that the title also resonates very strongly with my own personality. I kept returning to Majuli until I became part of it, and I began to tell the stories of the people—their struggles and joys—through my own human experiences. I believe there are places that can never be fully understood, because there are layers of history (quite literally, layers of sediment in the riverbed) that would take a lifetime to untangle. But a visual project like this offers a powerful opportunity for the author to better understand both the world and themselves.

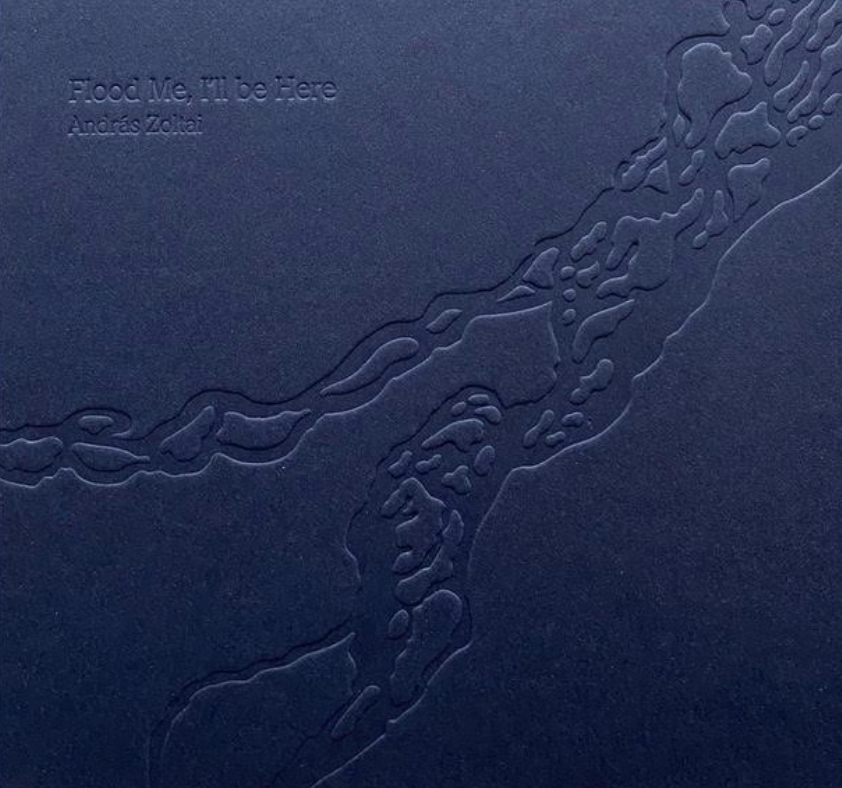

Editor’s note: The new book, Flood Me, I’ll be Here, will be launched during the opening week of Les Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles, followed by an event at the Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Center in Budapest. We discovered this remarkable work during portfolio reviews with Eastern European photographers in Budapest.