Can you hear a photograph? A shaking, shimmering beat escaping from its edges? The sound of the van coming down a dusty road or the quiet lap of water against a body floating? The murmur of a crowd as it waits for a show to begin? In Indian artist Abhishek Khedekar’s experimental project Tamasha you certainly can. Photography may be a visual medium but one of its strengths is its ability to transcend that, activating the other senses and bringing a viewer into a scene.

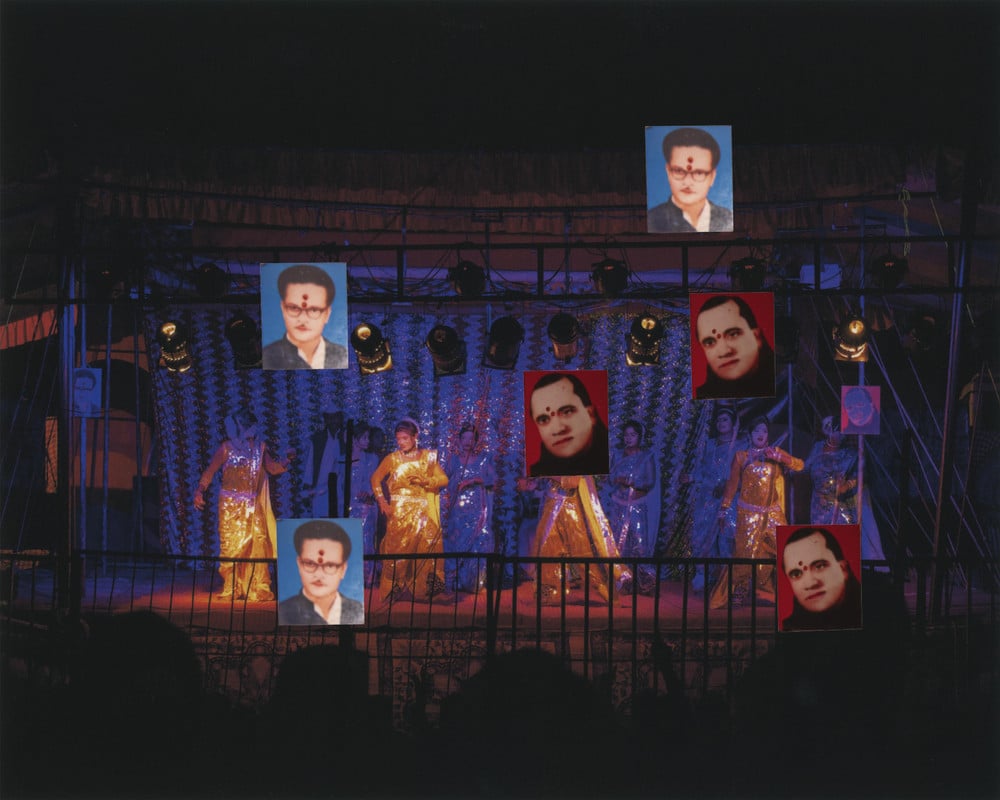

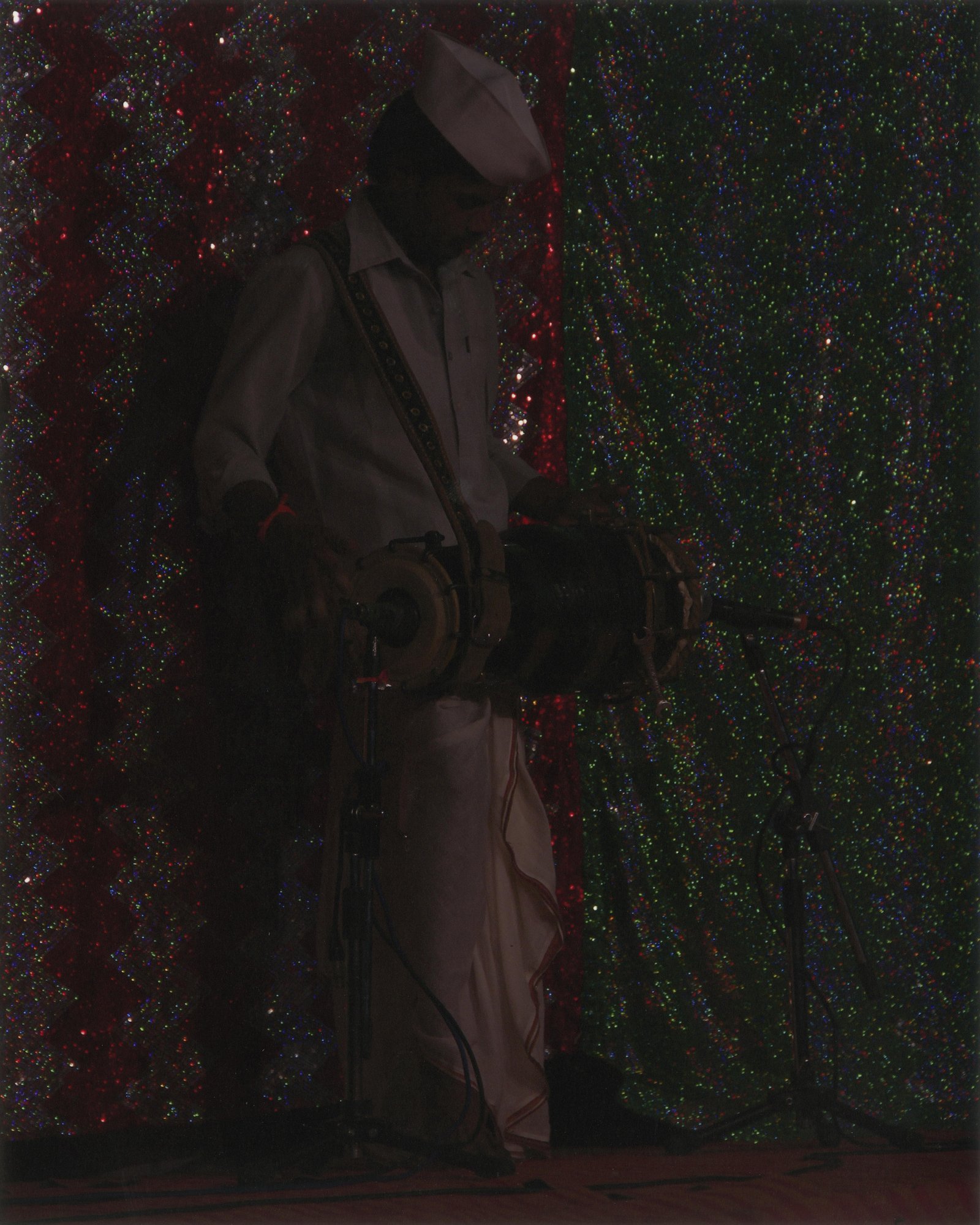

For Khedekar, an immersive approach was key to capturing the experience behind Tamasha. The term, a loan word from Persian, means performance or a grand show. In the photographer’s project, it refers to a nomadic troupe that travels from village to village across the Indian state of Maharashtra performing a mix of traditional song and dance, comedy and drama, oftentimes addressing socio-political issues. The members come from various walks of life but the majority are from the marginalized Dalit caste, amongst whom Tamasha has been passed down across generations.

Editor’s Note: Abhishek Khedekar’s project Tamasha was short-listed in the Humanity category of LensCulture’s New Visions Awards 2025. See all of the winners and short-listed projects here.

Khedekar trains his camera on the performances as well as the various facets of their daily lives, from the familial atmosphere in the run-up to a show to the discrimination they face from the audience—the very same people they entertain. The troupe becomes a family unit and it took the photographer time to be accepted, but the camera proved to be a powerful way in. “At the beginning, they were a bit conscious of the camera. After a point, they thought ‘he’s taking pictures of everything’ and then it became, ‘Okay, he’s just walking around. He’s one of us.’” At one point, Khedekar even appeared in a performance, fittingly as a photographer in a wedding scene.

He came to know the members of the troupe and their various connections. “The electrician told me, ‘Oh, my mother! She’s also performing Tamasha, she’s a singer. I was born in Tamasha. Now I do all the electrical work. But I perform as a singer also, sometime in the evenings.’ Then I met another person who was a dancer. She told me that she ran away from home and started working here,” Khedekar explains. “People took time to open up. They said, ‘Okay, don’t mention my name here, because, in some villages, they look down on the performance because we live a nomadic life.’” What started as a desire to document a shifting art form became a quest to capture a fuller perspective, informed by discrimination, expression, and community.

Much like family, Khedekar experienced how members looked out for one another, with performers pointing out villages to be wary of. “At one place I had an experience of discrimination. A basic need is that you have to wash your face, brush your teeth, and take a bath, but unless your (water) tanker comes, you are just sitting there, waiting. There was a water tap I was trying to access, and some villagers said, ‘Oh, you don’t use this water. Wait for your water.’ I thought maybe there was a shortage of water or something. But then a friend of mine, who is a manager, said, ‘That’s not it. There is still, in some villages, a caste system.’”

In the beginning, Tamasha was performed by women of the Dalit caste, and while that may slowly be changing, preconceptions and prejudices have a way of holding on. “During the performance at night, these people were cherished. And yet during the daytime, their basic needs were neglected,” Khedekar says.

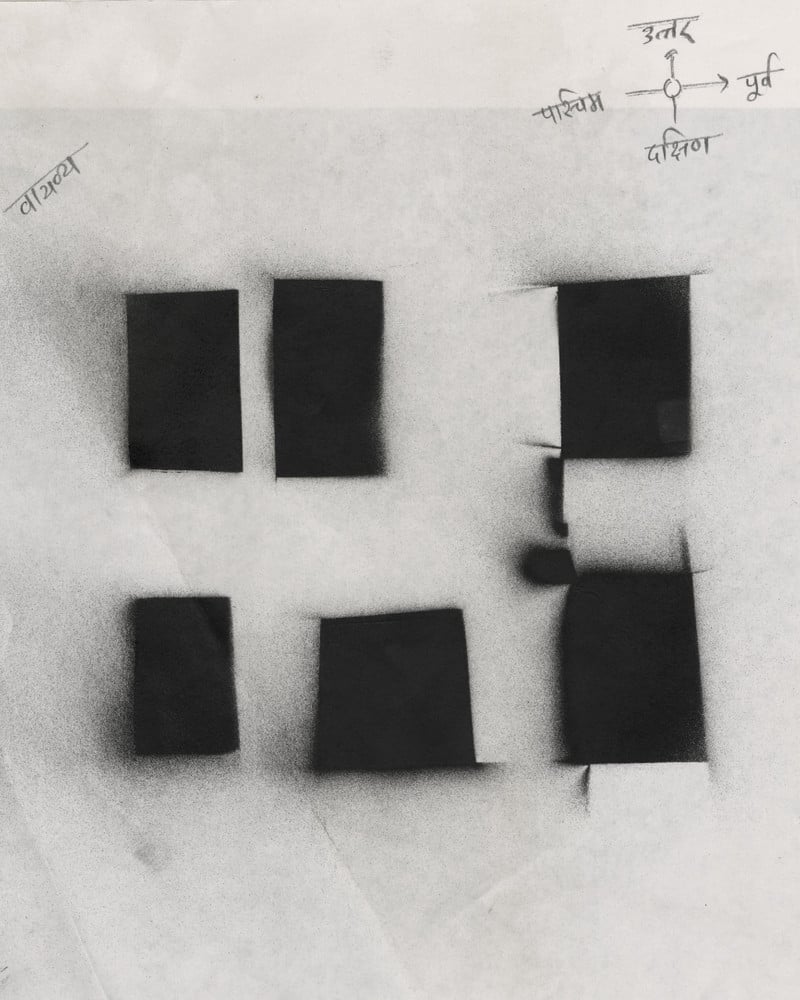

To capture the breadth and complexity of Tamasha as well as the socio-cultural realities it occurs within, Khedekar felt he had to expand the work. He asked himself, “What is my experience of Tamasha? What is my experience towards the discrimination?” He uses the term ‘docu-fiction’ to describe the process he landed on. Accompanying his documentary-style photographs are collages and interventions. “I wanted to express, through the collages, the nomadic life of the troupe. I started staging or constructing images, asking somebody to hold a particular backdrop so I could enhance the particular thing I want to focus on, which may be neglected or forgotten again.”

Amidst portraits of performers and preparations for the show, there are props, cut-out images, and soil strewn on a photograph of a trunk. “Tamasha was an education for me. I was learning to understand different mediums,” Khedekar notes. “As an art form, it has been happening from the 18th century on and still exists. The form is changing drastically. People need different things now. They don’t want traditional songs anymore. I will not say it will disappear completely because it will keep going. But to preserve that, I think that I played a small role in photographing it.”

In working across a diverse mode of image-making, Khedekar has created a project that speaks in the voice of Tamasha—a sensorial sprawling, colorful, and communal experience. The magic occurs when the series embraces the camp ethos of putting on a show whilst not shying away from the real challenges its performers face.